Seeing and being

Preface

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

7. The man who sees everything

Imagine a visually omniscient man (or being of some sort) who sees everything that happens across both space and time.

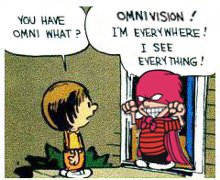

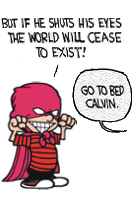

We may take this in a fairly innocent way to begin with, without overthinking the matter unduly. Just think of a comic-book superhero, say, who possesses the gift of omnivision. So this being has something like God’s powers of vision. He is always apprised of everything (visible) that transpires within the universe – past, present and future.

To keep the discussion manageable, it would help if reality consisted entirely of visible events. So let’s temporarily pretend that invisible events like thunderclaps and wafting odours never occur. (We might also include microsopic events and the happenings within a black hole, etc. – I won’t try to compile a list.) Alternatively, pretend that these things are visible – that would also do. The pretence is relatively harmless since it may be relinquished later – when we generalize from seeing to knowing.

Even with these clarifications, it is not easy to imagine the massive visual powers of our mythical being. After all, most people have difficulty imagining the vision even of a stick insect with compound eyes.

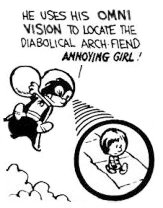

How much harder then to imagine what it must be like to be all-seeing. Mercifully, however, we need only to imagine enough for the purpose. The question we really want to ask is this – would an omnivisual being have any use for the concept of seeing?

This unusual question arises because our superhero sees everything that happens across both space and time. Nothing ever escapes his gaze, nor does he ever have a false vision, we might add. So the distinction between something’s being the case and his seeing it to be the case is liable to seem (from his point of view) like a distinction without a difference.

So a natural first suggestion, curiously enough, is that an omnivisual being would have no use for the distinction between seeing and being, and would thus not be disposed to draw it. At least, so far as I can see, there is no immediate reason why he would be compelled to draw the distinction.

This natural first suggestion, when suitably qualified, seems to me potentially sound (a good suggestion) and I should like at once to explore its implications. But the matter is a little delicate and we should probably move slowly. Let me first address two immediate concerns with the suggestion.

First, it may not be sufficiently clear what the suggestion is meant to amount to, even to begin with. Omnivision aside, we are being asked to imagine a (sighted and intelligent) person who does not distinguish seeing from being, i.e., between something’s being the case and his seeing it to be the case.

But what would it be like for a sighted and intelligent person not to make such a basic distinction? It is not clear what state of mind we are being asked to imagine here.

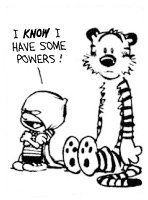

Second, the suggestion may (in any case) seem doubtful. It would entail, among other things, that this being would be unaware of his own powers. Thus, he would be unable to think, “Wow, I see everything,” let alone revel in his visual prowess, because this would require him (at a minimum) to distinguish seeing from being, which distinction he (supposedly) does not even recognize.

But it is a little hard to believe that he can be barred from recognizing that he sees everything simply because he sees everything. —Who would want to be this superhero?

Let me first address this second concern as this will help clarify the larger nature of our investigation.

The omnivisual being is meant to help us understand why we distinguish the concepts of seeing and being. As explained previously, understanding why we do so seems like a promising way of clarifying the vexing concept of seeing – our original target. We have yet to attain the desired understanding, but it helps to remember that we are starting by admitting that we don’t quite know what “seeing” is.

Now, to probe the distinction between seeing and being, our strategy is simply to consider an extreme case, where the distinction is on the verge of breaking down – close to losing its rationale. The hope is for this to throw light on the point of making the distinction in the first place. The case of the omnivisual being was meant, of course, to be just such a case – a potential case of such conceptual collapse. (A decent candidate, at least.) Our suspicion was that an omnivisual being would have no (immediate) need to distinguish something’s being the case from his seeing it to be the case, since it is in his nature to see precisely everything that is the case. In other words, he has no evident use for the distinction – no apparent call to make it – whereupon the distinction, from his point of view, appears to teeter on the desired verge of collapse.

Admittedly, we cannot claim to have proven that the distinction will so teeter. Our reasons for this were fairly swift, after all. How can we be sure that it will indeed teeter? Our superhero might rise up and protest, “What’s all the fuss about? I can easily make the distinction and apply it to my own case.” Or someone else might offer this protest on his behalf.

In a word, the considerations above might be thought too superficial to prove that an all-seeing being would fail to distinguish the act of seeing from the fact of being, i.e., even in the first instance. —This is the essential protest.

This protest is based on a misunderstanding, however, since we are not trying to “prove” anything at this stage, but are merely exploring a possible origin of the distinction between seeing and being. (The omnivisual being raises an “initial suspicion” as to the genesis of the distinction, which seems worth our while to explore.) The protest would be understandable if it was based on a firm grasp of the concept of seeing. —We could then stand assured that an omnivisual being would have no trouble distinguishing seeing from being, and I would be the first to abandon this line of investigation. But this is not our situation. Nobody has a firm enough grasp of seeing to be able to pronounce on such an anomalous case as that of an all-seeing being. So I plan simply to explore the suspicion and see where it leads. (The “proof” will be in the pudding.)

In any case, I do not consider it (ultimately) impossible for an omnivisual being to be aware of his own visual powers. But I do think that some thought is required to understand how this possibility might come to pass – i.e., to understand how an all-seeing being might come to acquire the distinction between seeing and being, and thereafter to apply it to his own case. For it is not immediately apparent why he would have any use for the distinction, as per the initial suspicion above. (But I will say more on this later.)

Let me turn now to the first concern mooted above, viz., the need to be clearer on the content of the “initial suspicion” that we are proposing to explore. For the thought here being paraded – of a sighted and intelligent person’s not distinguishing seeing from being – is not particularly easy to grasp, as previously noted. What on earth would it be like not to make this distinction? We should begin by clarifying what we are dealing with here.

For this purpose, it will be useful to compare our hypothetical case with a considerably more familiar case that exhibits very similar characteristics. It might be thought incredible that there could be such a case, but there is in fact one – the case of ordinary bodily pain. It is very useful for our purposes.

In most daily contexts, we do not distinguish between there being a pain in our hand (say) and our feeling the pain. The pain is just the feeling, one is apt to say. Murat Aydede puts it this way:

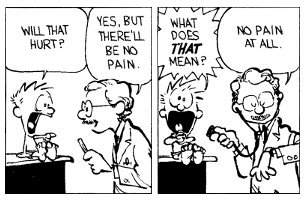

There are exceptions to this observation, no doubt. Having applied an anaesthetic, a doctor might quite ordinarily say to a patient, “Soon you won’t feel the pain,” apparently cleaving the being of the pain apart from its feeling. This kind of talk can make sense too and there are other such cases as well – though not perhaps the jokey one shown in the cartoon.

The ordinary practice of not making the distinction, however, is the right place to begin and I would like to focus on this here. Why do we ordinarily not make the distinction?

A traditional answer is that pains are mental events, i.e., they occur entirely in our minds. And since we are ordinarily apprised of everything that occurs in our minds, there will be no gap, as it were, between a pain’s existing in one’s mind and one’s knowing about it. In other words, esse est percipi for pains.

This sort of answer might have been given by an early modern philosopher, but it is of no use to us because it takes the concept of mind for granted, whereas a concept of this sort is precisely what we are trying to get clear on.

This sort of answer might have been given by an early modern philosopher, but it is of no use to us because it takes the concept of mind for granted, whereas a concept of this sort is precisely what we are trying to get clear on.

We can get a more useful answer, however, if we turn things around and start from the fact that we normally take ourselves to be omniscient with respect to our own bodily pains. (Why we tend to assume this will not matter here, so long as we do not give the early modern answer. A reasonable alternative might invoke the evolutionary value of this ability.) This seems to explain why we don’t normally distinguish a bodily pain from our feeling of it. The reason, as it were, is that we are always apprised of our bodily pains, and so have no ordinary need to distinguish the being of the pain from the feeling – the pain is just the feeling.

So the curious “subjective ontology” of bodily pains may have a rather simple explanation, after all. It may have nothing to do with the fact that bodily pains exist in our minds, which might sound like a contradiction, but more to do with the fact that we always know about our bodily pains. Or so I am suggesting.

This model is useful because it also helps us understand what it might be like to be an omnivisual being, at least in the first instance. Such a being will tend not to distinguish seeing from being in the same way (and for the same reason) that we tend not to distinguish the feeling of a pain from its being. In our case, the reason is that we always feel our pains. In his case, the reason is that he always sees everything.

We may expect, therefore, that the whole world will have a “subjective ontology” for this being in exactly the way that pains have a subjective ontology for us.

This gives us a useful handle on the state of mind of an omnivisual being. Ontologically speaking, his phenomenon of seeing will be very much like our phenomenon of pain. Just as we tend not to distinguish feeling a pain from the pain itself, he will tend not to distinguish seeing the world from the world itself.

The question now is where this is supposed to lead.

Imagine a visually omniscient man (or being of some sort) who sees everything that happens across both space and time.

We may take this in a fairly innocent way to begin with, without overthinking the matter unduly. Just think of a comic-book superhero, say, who possesses the gift of omnivision. So this being has something like God’s powers of vision. He is always apprised of everything (visible) that transpires within the universe – past, present and future.

To keep the discussion manageable, it would help if reality consisted entirely of visible events. So let’s temporarily pretend that invisible events like thunderclaps and wafting odours never occur. (We might also include microsopic events and the happenings within a black hole, etc. – I won’t try to compile a list.) Alternatively, pretend that these things are visible – that would also do. The pretence is relatively harmless since it may be relinquished later – when we generalize from seeing to knowing.

Even with these clarifications, it is not easy to imagine the massive visual powers of our mythical being. After all, most people have difficulty imagining the vision even of a stick insect with compound eyes.

How much harder then to imagine what it must be like to be all-seeing. Mercifully, however, we need only to imagine enough for the purpose. The question we really want to ask is this – would an omnivisual being have any use for the concept of seeing?

This unusual question arises because our superhero sees everything that happens across both space and time. Nothing ever escapes his gaze, nor does he ever have a false vision, we might add. So the distinction between something’s being the case and his seeing it to be the case is liable to seem (from his point of view) like a distinction without a difference.

So a natural first suggestion, curiously enough, is that an omnivisual being would have no use for the distinction between seeing and being, and would thus not be disposed to draw it. At least, so far as I can see, there is no immediate reason why he would be compelled to draw the distinction.

Note. There might be various “secondary” reasons that might eventually force the distinction upon him. I discuss this below.

This natural first suggestion, when suitably qualified, seems to me potentially sound (a good suggestion) and I should like at once to explore its implications. But the matter is a little delicate and we should probably move slowly. Let me first address two immediate concerns with the suggestion.

First, it may not be sufficiently clear what the suggestion is meant to amount to, even to begin with. Omnivision aside, we are being asked to imagine a (sighted and intelligent) person who does not distinguish seeing from being, i.e., between something’s being the case and his seeing it to be the case.

But what would it be like for a sighted and intelligent person not to make such a basic distinction? It is not clear what state of mind we are being asked to imagine here.

Second, the suggestion may (in any case) seem doubtful. It would entail, among other things, that this being would be unaware of his own powers. Thus, he would be unable to think, “Wow, I see everything,” let alone revel in his visual prowess, because this would require him (at a minimum) to distinguish seeing from being, which distinction he (supposedly) does not even recognize.

But it is a little hard to believe that he can be barred from recognizing that he sees everything simply because he sees everything. —Who would want to be this superhero?

Let me first address this second concern as this will help clarify the larger nature of our investigation.

The omnivisual being is meant to help us understand why we distinguish the concepts of seeing and being. As explained previously, understanding why we do so seems like a promising way of clarifying the vexing concept of seeing – our original target. We have yet to attain the desired understanding, but it helps to remember that we are starting by admitting that we don’t quite know what “seeing” is.

Now, to probe the distinction between seeing and being, our strategy is simply to consider an extreme case, where the distinction is on the verge of breaking down – close to losing its rationale. The hope is for this to throw light on the point of making the distinction in the first place. The case of the omnivisual being was meant, of course, to be just such a case – a potential case of such conceptual collapse. (A decent candidate, at least.) Our suspicion was that an omnivisual being would have no (immediate) need to distinguish something’s being the case from his seeing it to be the case, since it is in his nature to see precisely everything that is the case. In other words, he has no evident use for the distinction – no apparent call to make it – whereupon the distinction, from his point of view, appears to teeter on the desired verge of collapse.

Admittedly, we cannot claim to have proven that the distinction will so teeter. Our reasons for this were fairly swift, after all. How can we be sure that it will indeed teeter? Our superhero might rise up and protest, “What’s all the fuss about? I can easily make the distinction and apply it to my own case.” Or someone else might offer this protest on his behalf.

In a word, the considerations above might be thought too superficial to prove that an all-seeing being would fail to distinguish the act of seeing from the fact of being, i.e., even in the first instance. —This is the essential protest.

This protest is based on a misunderstanding, however, since we are not trying to “prove” anything at this stage, but are merely exploring a possible origin of the distinction between seeing and being. (The omnivisual being raises an “initial suspicion” as to the genesis of the distinction, which seems worth our while to explore.) The protest would be understandable if it was based on a firm grasp of the concept of seeing. —We could then stand assured that an omnivisual being would have no trouble distinguishing seeing from being, and I would be the first to abandon this line of investigation. But this is not our situation. Nobody has a firm enough grasp of seeing to be able to pronounce on such an anomalous case as that of an all-seeing being. So I plan simply to explore the suspicion and see where it leads. (The “proof” will be in the pudding.)

In any case, I do not consider it (ultimately) impossible for an omnivisual being to be aware of his own visual powers. But I do think that some thought is required to understand how this possibility might come to pass – i.e., to understand how an all-seeing being might come to acquire the distinction between seeing and being, and thereafter to apply it to his own case. For it is not immediately apparent why he would have any use for the distinction, as per the initial suspicion above. (But I will say more on this later.)

Let me turn now to the first concern mooted above, viz., the need to be clearer on the content of the “initial suspicion” that we are proposing to explore. For the thought here being paraded – of a sighted and intelligent person’s not distinguishing seeing from being – is not particularly easy to grasp, as previously noted. What on earth would it be like not to make this distinction? We should begin by clarifying what we are dealing with here.

For this purpose, it will be useful to compare our hypothetical case with a considerably more familiar case that exhibits very similar characteristics. It might be thought incredible that there could be such a case, but there is in fact one – the case of ordinary bodily pain. It is very useful for our purposes.

In most daily contexts, we do not distinguish between there being a pain in our hand (say) and our feeling the pain. The pain is just the feeling, one is apt to say. Murat Aydede puts it this way:

Pains ... seem to be subjective in the sense that their existence depends on feeling them. There is an air of paradox when someone talks about unfelt pains. One is naturally tempted to say that if a pain is not being felt by its owner then it does not exist. (‘Pain,’ section 1.2.)Wittgenstein also has a famous passage:

This is the same kind of observation and it rings true for many people.It can’t be said of me (except perhaps as a joke) that I know I am in pain. What is it supposed to mean—except perhaps that I am in pain? (Investigations, §246.)

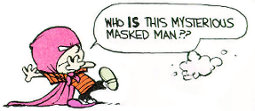

There are exceptions to this observation, no doubt. Having applied an anaesthetic, a doctor might quite ordinarily say to a patient, “Soon you won’t feel the pain,” apparently cleaving the being of the pain apart from its feeling. This kind of talk can make sense too and there are other such cases as well – though not perhaps the jokey one shown in the cartoon.

The ordinary practice of not making the distinction, however, is the right place to begin and I would like to focus on this here. Why do we ordinarily not make the distinction?

A traditional answer is that pains are mental events, i.e., they occur entirely in our minds. And since we are ordinarily apprised of everything that occurs in our minds, there will be no gap, as it were, between a pain’s existing in one’s mind and one’s knowing about it. In other words, esse est percipi for pains.

We can get a more useful answer, however, if we turn things around and start from the fact that we normally take ourselves to be omniscient with respect to our own bodily pains. (Why we tend to assume this will not matter here, so long as we do not give the early modern answer. A reasonable alternative might invoke the evolutionary value of this ability.) This seems to explain why we don’t normally distinguish a bodily pain from our feeling of it. The reason, as it were, is that we are always apprised of our bodily pains, and so have no ordinary need to distinguish the being of the pain from the feeling – the pain is just the feeling.

So the curious “subjective ontology” of bodily pains may have a rather simple explanation, after all. It may have nothing to do with the fact that bodily pains exist in our minds, which might sound like a contradiction, but more to do with the fact that we always know about our bodily pains. Or so I am suggesting.

This model is useful because it also helps us understand what it might be like to be an omnivisual being, at least in the first instance. Such a being will tend not to distinguish seeing from being in the same way (and for the same reason) that we tend not to distinguish the feeling of a pain from its being. In our case, the reason is that we always feel our pains. In his case, the reason is that he always sees everything.

We may expect, therefore, that the whole world will have a “subjective ontology” for this being in exactly the way that pains have a subjective ontology for us.

This gives us a useful handle on the state of mind of an omnivisual being. Ontologically speaking, his phenomenon of seeing will be very much like our phenomenon of pain. Just as we tend not to distinguish feeling a pain from the pain itself, he will tend not to distinguish seeing the world from the world itself.

The question now is where this is supposed to lead.

Menu

What’s a logical paradox?

What’s a logical paradox? Achilles & the tortoise

Achilles & the tortoise The surprise exam

The surprise exam Newcomb’s problem

Newcomb’s problem Newcomb’s problem (sassy version)

Newcomb’s problem (sassy version) Seeing and being

Seeing and being Logic test!

Logic test! Philosophers say the strangest things

Philosophers say the strangest things Favourite puzzles

Favourite puzzles Books on consciousness

Books on consciousness Philosophy videos

Philosophy videos Phinteresting

Phinteresting Philosopher biographies

Philosopher biographies Philosopher birthdays

Philosopher birthdays Draft

Draftbarang 2009-2024  wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine