Draft

There is surprisingly little discussion of whether teletransportation can be verified (or falsified) empirically. I think the question is more interesting than most people realize..

There is surprisingly little discussion of whether teletransportation can be verified (or falsified) empirically. I think the question is more interesting than most people realize..

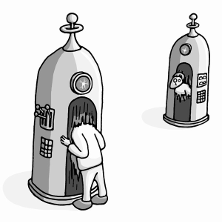

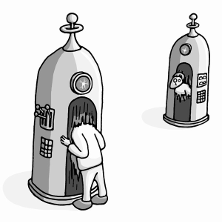

The issue is whether the person who emerges from the transporter is the same as the person who entered; or just a freshly-created lookalike, the one who entered having died. Empirically speaking, what everyone agrees on is this: we cannot determine the answer “from the outside,” i.e., from a third-person vantage point. It would be futile to observe someone else enter the machine and thereafter “check” if that same person emerged on Mars: there would be no telling if the person who emerged was the same as the one who entered.

The interesting question however is whether we can determine the answer “from the inside,” from the first-person point of view. At risk to your own life, could you not try the machine out for yourself in order to see what happens?

This simple first-person empirical check does appear to work in at least one type of case. If there was such a thing as an afterlife, then, if the machine killed you, you’d find yourself waking up in some fiery place like purgatory (say), and you’d realize (let’s presume) that you were dead. Thus:

Kathleen V. Wilkes, Real People (1988), p. 46, n. 28. As quoted in Marya Schechtman, ‘Experience, Agency and Personal Identity,’ in Ellen Frankel Paul et al. (eds.), Personal Identity (2005), p. 8. Captain Kirk, so the story goes, disintegrates at place p and reassembles at place p*. But perhaps, instead, he dies at p and a doppelgänger emerges at p*. What is the difference? One way of illustrating the difference is to suppose there is an afterlife: a heaven, or hell, increasingly supplemented by yet more Captain Kirks all cursing the day they ever stepped into the molecular disintegrator.

This is Kathleen Wilkes, lamenting the “inconclusive nature” of science fantasy. But her words are to our purpose too: if the transporter killed you, then you could discover this by trying it out, assuming there was such a thing as an afterlife. Of course, if there was no afterlife, then you’d learn nothing: you’d just lose consciousness and it’d be over. But the potential for falsification is clearly there since we cannot in general rule out the possibility of an afterlife.

If falsification of teletransportation is thus possible, what of verification? What happens if the machine worked and really did “send” you to Mars? You’d press the button and find yourself waking up on Mars. Would this assure you in the same way that teletransportation was real and that you really had been transported to Mars? Take Parfit’s story above:

I press the button. As predicted, I lose and seem at once to regain consciousness, but in a different cubicle. Examining my new body, I find no change at all. Even the cut on my upper lip, from this morning’s shave, is still there.

I press the button. As predicted, I lose and seem at once to regain consciousness, but in a different cubicle. Examining my new body, I find no change at all. Even the cut on my upper lip, from this morning’s shave, is still there.

Would this satisfy Parfit himself, if no one else, that the machine had worked? Would it constitute an empirical verification of teletransportation?

As we know, the matter is not that simple, because of the following obvious snag. Even if the machine did work, and you did find yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether you were the person who entered the machine, or whether that person died, and you were just a freshly-minted lookalike with false beliefs of having previously entered the machine. After all, anyone—real or copy—who emerged on Mars would “remember” having earlier entered the machine on Earth. So you’d be none the wiser as to whether you were “real” or “copy,” and thus none the wiser as to whether the machine had really worked.

For example, in Dan Dennett’s story, a woman on Mars with a broken spaceship uses a teletransporter to get back to Earth. Upon reuniting with her daughter Sarah, it “hits her”:

Am I, really, the same person who kissed this little girl good-bye three years ago? Am I this eight-year-old child’s mother or am I actually a brand-new human being, only several hours old, in spite of my memories—or apparent memories—of days and years before that? Did this child’s mother recently die on Mars, dismantled and destroyed in the chamber of a Teleclone Mark IV? Did I die on Mars? No, certainly I did not die on Mars, since I am alive on Earth. Perhaps, though, someone died on Mars—Sarah’s mother. Then I am not Sarah’s mother. But I must be! The whole point of getting into the Teleclone was to return home to my family! But I keep forgetting; maybe I never got into that Teleclone on Mars. Maybe that was someone else—if it ever happened at all. Is that infernal machine a teleporter—a mode of transportation—or, as the brand name suggests, a sort of murdering twinmaker?

Am I, really, the same person who kissed this little girl good-bye three years ago? Am I this eight-year-old child’s mother or am I actually a brand-new human being, only several hours old, in spite of my memories—or apparent memories—of days and years before that? Did this child’s mother recently die on Mars, dismantled and destroyed in the chamber of a Teleclone Mark IV? Did I die on Mars? No, certainly I did not die on Mars, since I am alive on Earth. Perhaps, though, someone died on Mars—Sarah’s mother. Then I am not Sarah’s mother. But I must be! The whole point of getting into the Teleclone was to return home to my family! But I keep forgetting; maybe I never got into that Teleclone on Mars. Maybe that was someone else—if it ever happened at all. Is that infernal machine a teleporter—a mode of transportation—or, as the brand name suggests, a sort of murdering twinmaker?

So it seems that, if the machine worked, you could not discover this even by trying it out for yourself. This may be why the question is seldom discussed of whether teletransportation is subject to empirical test. At least where verification of the phenomenon is concerned—and this is arguably the more important case—the answer may be thought to be obviously no.

This may be thought to settle the matter but, in fact, I will suggest now that the foregoing sceptical view is confused, and ultimately incorrect. If the teletransporter works, I believe that you can verify this by trying the machine out for yourself.

The sceptic claims that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether your memory of having entered the machine was genuine or false. You wouldn’t know if you were the person who originally entered the machine, or just a freshly-minted copy with false memories of having done so. So you’d be unable to tell if the machine had worked. (If you happened to be the copy, the machine would in fact have failed.)

The alleged threat here is that of “being the copy.” As you wake up on Mars, the thought that you might be the copy is supposed to give you pause. But for the copy, you could just go by your memory of having entered the machine and declare that the machine had worked. But—wait—you might be the copy! Then your memory would be false and the machine would in fact have failed! You’d be in danger of making a wrong judgement here if you went by your “memory.”

This reasoning is confused. Consider first that it would not be possible for you to enter the machine and then wake up on Mars in the body of your copy. This could not happen since your copy and you are two distinct individuals. So you don’t have to worry about the touted possibility of “being the copy”: there is no such possibility. Put another way, there is no danger of you—the person originally entering the machine—waking up on Mars with a false memory of having entered the machine. Nor is there any danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. These things are impossible within the context of our story.

It will be objected that the touted possibility (“You might be the copy”) is not that of you entering the machine and then waking up on Mars in the body of your copy, which would of course be impossible, but that of the person now waking up on Mars—the one being addressed (“you”)—being the copy. This latter is certainly possible since if the machine should fail, the copy would wake up on Mars, and this might be who the sceptic happens now to be addressing.

the copy would wake up on Mars, and this might be who the sceptic happens now to be addressing.

But this doesn’t help matters. If you were the copy in this sense, there’d still be no “danger” of making a wrong judgement. The reason is that your false memory (and attendant danger) would now be irrelevant: it wouldn’t in this case matter if you went by your “memory” and judged wrongly that the machine had worked. It wouldn’t matter because, relative to our purposes, nothing turns on whether the copy is able to accurately divine his true situation.

the copy is able to accurately divine his true situation.

Recall that we were trying to ascertain whether you, the person who originally entered the machine, would be able to tell that the machine had worked, should you find yourself waking up on Mars. The one being interrogated here is you: would you be able to tell? Now, should the machine fail, you’d die, and your copy would awaken on Mars, but notice that we have no essential interest in whether your copy would (in that event) be able to tell that the machine had failed. In a different context, we might care about this—see shortly below—but if we are trying simply to establish whether teletransportation can be verified in the first person, i.e., by you, then it doesn’t matter if your copy, should he come into existence, gets it wrong. It doesn’t matter what your copy judges; he is not being interrogated at all. What matters is that you, the person who entered the machine, get it right.

For comparison, consider a different case where both you and your copy are equally subject to interrogation, so that it matters that he gets it right too. Consider the scenario once mentioned by Russell wherein the whole world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. How do you know that this did not just happen?

unreal past. How do you know that this did not just happen?

Here, as in our case, either you are who you remember yourself to be (the real you) or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past (the copy). But notice here that either way, you are being interrogated by the sceptic: did the world just spring into being? The sceptic claims that “you” cannot reliably tell. In this case, it seems to me that the sceptic has a point because the threat of “being the copy” is now genuine. If you just went by your memory, you might get it wrong, because you might be the copy. This is exactly as before but, this time, getting it wrong qua being the copy is just as bad as getting it wrong qua being real. This is clear from the context and it makes all the difference.

It’s as though God had randomly subjected either the real person or the copy to interrogation, creating the appropriate world for the purpose. It should be clear that this randomly chosen individual (“you”) could do no better than chance in divining whether or not the world had just sprung into being. God might demonstrate this by conducting repeated trials: in the long run, “you” would be able to divine the correct answer only half the time, at best.

Likewise for Dennett’s protagonist above, who wonders whether she’s real or copy, whether the machine had worked or failed. This case is close to ours, but the difference is that Dennett’s protagonist means to be interrogating herself regardless of whether she’s real or copy. (She wants to know either way.) This is again clear from the context, and scepticism now has a foothold for the same reason as before: getting it wrong qua being the copy would be just as bad as getting it wrong qua being real. So, in this case too, it seems to me that the touted scepticism is warranted: Dennett’s protagonist is unable to tell whether she’s real or copy. (God might again demonstrate this by means of repeated trials.)

Neither Russell’s nor Dennett’s case should be confused with ours. Our case involves seeing if you can tell whether the teletransporter works by trying it out for yourself. So, essentially, only you, the person who enters the machine, stand to be interrogated over whether or not the machine had worked. Your copy, should he materialize, is essentially irrelevant.

Indeed, your copy here is something of an interloper, who pilfers your memories and runs into trouble as a result. If he wakes up on Mars and believes that the machine had worked, he may—to his undoing—try to schedule a “return” trip, etc. None of this has anything to do with you: you could never get into such trouble. Put another way, should God conduct repeated trials to see whether you could tell that the machine had worked (whenever it did), God would set aside worlds where the person waking up on Mars was your copy, and focus on worlds where this person was you, the one who entered the machine. You’d then be interrogated on whether or not the machine had worked. Could you reliably tell? Well, if you always went by your memory, you’d always get it right.

So we’re back where we started, but armed with the realization that your copy is a red herring. If you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you may simply go by your apparent memory, judge that the machine had worked, and not worry about “being the copy.” Your judgement would be bound to be correct, even if there was some sense—the (irrelevant) Russell-Dennett one—in which “you” couldn’t tell whether or not you were the copy. It’d be bound to be correct just because it was you, the person who originally entered the machine, who was making the judgement. Even God, by repeated test, would have to acknowledge that you could reliably tell that the machine had worked. So should you so much as seem to find yourself waking up on Mars, you may be completely confident—indeed certain—that the machine had worked. You’d know that the machine had worked. “That’s what your copy would think!” an objector persists. But, no, this is the same mistake again: overlooking that, relative to our purposes, what your copy thinks or judges is immaterial.

My conclusion, therefore, is that if the teletransporter works, you can discover this by trying it out for yourself. You’d find yourself waking up on Mars and you’d know that you had survived and that the thing had worked. The objection, “Not so fast! You might be the copy!” is just confused. In one sense, as pointed out, you couldn’t possibly be the copy; in another, it would be irrelevant if “you” were, because it doesn’t matter if the copy gets it wrong. Notice also that, in this latter case, where the copy (“you”) wakes up on Mars and judges wrongly that the machine had worked, the real you might well find yourself waking up in purgatory (as before), realizing correctly that the machine had failed. This makes it even clearer that the misadventures of the copy are just irrelevant: the real you would always get it right. The sceptical objection seems to work only because it confuses our context with various other ones like Russell’s and Dennett’s above in which this sort of objection would work.

Does a teletransporter really work? The most convincing demonstration of this, it seems to me, would be a first-person empirical one. Just try out the machine and see. If it works, you’d find out. The natural thought that such a demonstration would be impossible is, I think, wrong.

Let me now show how this sort of empirical demonstration can be used to decide another vexing problem in this area, viz., the question of what happens in fission.

###############

------------

This may be thought to settle the matter but, in fact, I will suggest now that the foregoing sceptical view is more confused than correct. I believe that the sceptic has overlooked an important feature of our predicament.

The sceptic claims that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether your memory of having entered the machine was genuine or false. You wouldn’t know if you were the person who originally entered the machine, or just a freshly-minted copy with false memories of having done so. So you’d be unable to tell if the machine had worked. If you happened to be the copy, the machine would in fact have failed.

The alleged threat here is that of “being the copy.” As you wake up on Mars, the thought that you might be the copy is supposed to give you pause. But for the copy, you could just go by your memory of having entered the machine and declare that the machine had worked. But—wait—you might be the copy! Then your memory would be false and the machine would in fact have failed! You’d be in danger of making a wrong judgement here if you just went by your “memory.”

This threat of “being the copy” seems plausible at first sight, but I believe it is ultimately illusory. Note first that the sceptic cannot mean that you, the person who originally entered the machine, might be the copy. This would be impossible since you and your copy are distinct individuals. What the sceptic means rather is that the person now waking up on Mars—the one being addressed (“you”)—might be the copy. But this threat is illusory too, though in a more subtle way. If you were the copy in this sense, then it wouldn’t actually matter if you went by your memory and ended up judging wrongly that the machine had worked, because the ability of your copy to descry his true situation is nowhere under scrutiny here. This is what the sceptic seems to me to have overlooked.

Recall that we were trying to ascertain whether you, the person who originally entered the machine, would be able to tell that the machine had worked, should you find yourself waking up on Mars. The challenge here is being issued to you: can you tell? Now, should the machine fail, you’d die, and your copy would awaken on Mars, but notice that we have no essential interest in whether your copy would (in that event) be able to tell that the machine had failed. In a different context, we might care about this—see shortly below—but if we are trying simply to establish whether teletransportation can be verified in the first person, i.e., by you, then it doesn’t matter if your copy, should he come into existence, gets it wrong. No challenge is being issued to your copy at all. What matters is that you, the person who entered the machine, get it right.

To see the difference, consider a context where both you and your copy are “challenged,” so that it matters that he gets it right too. Consider the scenario once mentioned by Russell wherein the whole world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. How do you know that this did not just happen?

To see the difference, consider a context where both you and your copy are “challenged,” so that it matters that he gets it right too. Consider the scenario once mentioned by Russell wherein the whole world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. How do you know that this did not just happen?

Here, as in our case, either you are who you remember yourself to be (the real you) or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past (the copy). But notice here that either way, you are being challenged by the sceptic: did the world just spring into being? The sceptic claims that “you” cannot reliably tell which. In this case, I am inclined to side with the sceptic because the threat of being the copy is now genuine. If you just went by your memory, you might get it wrong, because you might be the copy. This is exactly as before but, this time, getting it wrong qua being the copy is just as bad as getting it wrong qua being real.

It is as though God were to pick either the real person or the copy at random to be thus challenged, creating the appropriate world for the purpose. This randomly chosen person (“you”) could clearly do no better than chance in divining whether or not the world had just sprung into being. God might demonstrate this by conducting repeated trials: in the long run, “you” would be able to divine the correct answer only half the time, at best.

In our case, in contrast, only the person who originally entered the machine is being tested, or challenged. The copy, should he come into existence, is irrelevant. Should God conduct repeated trials to see whether the person waking up on Mars could reliably tell whether or not the machine had worked, he’d ignore worlds where the person waking up on Mars was the copy, and focus on worlds where this person was the one who originally entered the machine. This person would then be challenged to say whether or not the machine had worked, the question being whether he can reliably tell.

And it should now be clear that if this person always went by his apparent memory and averred that the machine had worked, he’d always get it right! Even God would have to admit that he could reliably tell. In other words, if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you may simply go by your apparent memory, judge that the machine had worked, and not worry about “being the copy.” Your judgement would be bound to be correct, even if there was some sense (see below) in which you couldn’t tell whether or not you were the copy. It’d be correct just because it was you who was making the judgement. Should your copy find himself waking up on Mars and attempt the corresponding judgement, he’d get it wrong, but not you. You could never get this judgement wrong.

Put another way, there is no danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) And so you really should have no hesitation in judging that the machine had worked, should you so much as appear to find yourself waking up on Mars. Your judgement here could never be wrong, so you may confidently judge that you had survived the trip and that the machine had worked; indeed, you may be certain of it. In this sense, you’d know that the machine had worked, should you appear to find yourself waking up on Mars.

Put another way, there is no danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) And so you really should have no hesitation in judging that the machine had worked, should you so much as appear to find yourself waking up on Mars. Your judgement here could never be wrong, so you may confidently judge that you had survived the trip and that the machine had worked; indeed, you may be certain of it. In this sense, you’d know that the machine had worked, should you appear to find yourself waking up on Mars.

It may be thought that this is not a real case of knowing that the machine had worked. Waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t really know whether you were real or copy, and thus whether or not the machine had worked. What you’d know is that if you were copy, it wouldn’t matter what you judged (since, as before, the copy is not being tested), so you might as well judge that you were real and that the machine had worked. But you wouldn’t really know whether this was true. It’d just be a “safe” judgement to make, in that you could never be faulted, either way, for judging as much.

This is the same error as before, only in a different form. There is doubtless a sense in which “you” wouldn’t know whether you were real or copy—just as there was a sense in Russell’s case in which “you” wouldn’t know whether or not the universe had just sprung into being—but the unknowing person (“you”) here is the randomly chosen person previously mentioned: either you or your copy, picked at random. This person wouldn’t reliably be able to say whether they were real or copy, or whether the machine had worked or failed, or whether their memories were genuine or false, etc.

But you, on the other hand, the person who entered the machine, would know that you were real, in the same way that you’d know that the machine had worked. You could never get this wrong if you went simply by your memory: if God were to test you, he’d concur. It may also help to see it this way. Suppose that “you” were actually the copy, judging wrongly that the machine had worked. Then the real you would be somewhere else—in purgatory, let us assume—finding out that the machine had failed. This should make it clear that you really don’t have to worry about “being the copy”: in the only sense that matters, you could never be the copy: the two of you are different individuals.

You don’t have to worry about being the copy because you could never end up in your copy’s body. “But that’s exactly what your copy would think!,” you retort. But this again fails to see that what your copy would think is irrelevant.

Your copy is essentially an interloper who pilfers your memories and gets into all sorts of trouble because of that. For example, if he believes that the machine had worked, he may—to his downfall—try to schedule a “return” trip, etc. None of this has anything to do with you: you could never get into such trouble, nor are you obliged to protect your copy from harm.

It may be objected that—wait—you might turn out to be the copy, in which case your “confident judgement” would be badly wrong. Surely you’d need to rule out that you’re the copy in order to be confident that the machine had worked—but how could you do that? This is the same error again.

Imagine for a moment that there was no complication of any doppelgänger waking up on Mars, so that if the machine killed you, no one would wake up on Mars. Then, if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d know at once that the machine had worked. I take it that this needs no explanation. Now restore the complication of the doppelgänger: should the machine kill you, a copy of you would wake up on Mars with false memories of having entered the machine, and so on. The sceptic contends that, this time, if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell if you were real or copy, and thus be unable to tell if the machine had worked. (If you happened to be the copy, the machine would in fact have failed.)

This contention of the sceptic seems rather doubtful to me, even as it manages to sound both natural and familiar. It embodies a kind of thinking that works well in certain philosophical contexts, which is what lends it an air of plausibility. A little thought, however, will show that it doesn’t quite work in our case.

A context where it does work is the scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. How do you know that this did not just happen? In this case, as in ours, either you are who you remember yourself to be—the real you—or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past—the copy. In this case, I concur with the sceptic that there’s no saying which one. You simply can’t tell. Derivatively, you can’t tell whether or not the universe has just sprung into being.

A context where it does work is the scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. How do you know that this did not just happen? In this case, as in ours, either you are who you remember yourself to be—the real you—or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past—the copy. In this case, I concur with the sceptic that there’s no saying which one. You simply can’t tell. Derivatively, you can’t tell whether or not the universe has just sprung into being.

But this case of Russell’s differs from ours in one crucial respect. In Russell’s case, it doesn’t matter if you—the subject of the epistemic predicament—happen to be real or copy: either way, you are being “challenged” to say whether or not the universe has just sprung into being. And the sceptic is claiming that you cannot reliably tell which. More vividly, imagine God randomly picking either the real person or the copy to be challenged in this fashion, creating the appropriate world for the purpose. The claim is then that this randomly chosen person (“you”) can do no better than chance in divining whether he or she was real or copy. God might demonstrate this by conducting repeated trials: in the long run, “you” would be seen to divine the correct answer only half the time, at best.

In our case, however, things are different. Only the real you (and not the copy) is being challenged to say whether or not the machine had worked. After all, we were only trying to ascertain whether you—the person who entered the machine—would be able to tell that the machine had worked, should you find yourself waking up on Mars. This challenge is addressed to you: can you tell? Now, should the machine fail, you’d die, and your copy would awaken on Mars, but notice that there is no concern here with whether your copy would (in that event) be able to tell that the machine had failed. In a different context, we might be concerned with thist—see shortly below—but it doesn’t exist for our purposes. No challenge is being issued to your copy at all.

In divine terms, imagine God creating a world in which teletransportation works and then challenging someone who just took a trip in the machine to say whether or not

This makes a difference because you may now act as if you were in the “uncomplicated” case, where the potential existence of your copy was not an issue. Notice, in particular, that if you found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be bound to make a correct judgement if you judged that the machine had worked: you could never get this judgement wrong. So just ignore the complication of your copy, go by the appearances, and you’ll be fine. Put another way, there is no danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. The sceptic wants to protest here that “Hold on, you might be the copy,” implying that your judgement that the machine had worked might be wrong. But this doesn’t mean that you might wake up in your copy’s body, which is impossible. It means only that the person now waking up on Mars and judging that the machine had worked might be the copy. And the reply is that: yes, but it doesn’t matter if the copy’s judgement is wrong. This is what the sceptic seems to me to have overlooked. Our case cannot be compared with Russell’s.

Indeed, in our case, your copy is essentially an interloper who pilfers your memories and gets into all sorts of trouble because of that. For example, if he believes that the machine had worked, he may—to his downfall—try to schedule a “return” trip, etc. None of this has anything to do with you: you could never get into such trouble, nor are you obliged to protect your copy from harm.

Simply focus on your well-being, ignore the potential existence of your copy, and you will be fine. Suppose, for example, that you enter the machine and find yourself waking up on Mars. Then, exactly as in the uncomplicated way, you’d be able to tell that the machine had worked. The sceptic might protest that—hold on—you might be the copy, in which case the machine would have failed; how can you tell? But notice again that this is your copy’s problem, not yours. After all, the sceptic doesn’t mean that you—the person who entered the machine—might be the copy, which would be impossible, but that the person now waking up on Mars might be the copy. But this has nothing to do with you. You could never wake up on Mars and believe wrongly that the machine had worked. If you awaken on Mars and judge that the machine had worked, you’d be bound to be right. As before, simply focus on your well-being, ignore the potential existence of your copy, and you will be fine: the alleged complication of your copy is just a red herring.

Your concern is simply to establish that the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars. You can’t be concerned also with doing this in such a way that your copy be able to establish that the machine had failed should he find himself waking up on Mars! You think what. Got so much time ah?

If God were to recreate the whole situation repeatedly in such a way that the machine worked each time, then the person “challenged” to say whether or not the machine had worked would always be you, and never your copy. And you’d always be right if you said that the machine worked.

The sceptic claims that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether your memory of entering the machine was genuine or false. You’d be unable to tell if you were the person who originally entered the machine, or just a freshly-minted copy with false memories of having done so. As such, you wouldn’t know if the machine had worked. (If you happened to be the copy, the machine would in fact have failed.)

This reasoning is extremely natural. There is indeed a sense in which, if you woke up on Mars, you wouldn’t know whether the propositions mentioned above were true—e.g., you wouldn’t know whether the machine had worked—and the reasoning above captures this philosophically familiar sceptical sense well. But what the sceptic overlooks is that, in the nature of our case, there is another sense in which you would know that those propositions were true—e.g., you would know that the machine had worked. (The question then arises of which sense is pertinent for our purposes.)

To see this other sense, notice that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be bound to make a correct judgement if you judged that the machine had worked. Your judgement would be correct even if—as the sceptic contends—you couldn’t tell whether the machine had worked. It’d be correct just because it was you who was making the judgement. Should your copy find himself waking up on Mars and attempt the corresponding judgement, he’d get it wrong, but not you. You could never get this judgement wrong.

Indeed, it should be plain to you, as you press the button, that there is no danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) The sceptic would have you believe that if you pressed the button and found yourself waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t really know whether the machine had worked: should you judge as much, you could well be wrong. Now, in one sense, as I have conceded, this is correct, and I will say more about this sense below. But notice also the other sense in which there is absolutely no danger here of you being wrong. As just explained, should you find yourself waking up on Mars, you couldn’t be wrong in judging that the machine had worked. (Only your copy could get this judgement wrong.)

Indeed, it should be plain to you, as you press the button, that there is no danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) The sceptic would have you believe that if you pressed the button and found yourself waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t really know whether the machine had worked: should you judge as much, you could well be wrong. Now, in one sense, as I have conceded, this is correct, and I will say more about this sense below. But notice also the other sense in which there is absolutely no danger here of you being wrong. As just explained, should you find yourself waking up on Mars, you couldn’t be wrong in judging that the machine had worked. (Only your copy could get this judgement wrong.)

From this point of view, you should have no hesitation in judging that the machine had worked, should you so much as appear to find yourself waking up on Mars. Your judgement here could never be wrong, so you may confidently judge that you had survived the trip and that the machine had worked; indeed, you may be certain of it. In this sense, you’d know that the machine had worked, should you appear to find yourself waking up on Mars.

It may be objected that—wait—you might turn out to be the copy, in which case your “confident judgement” would be badly wrong. Surely you’d need to rule out that you’re the copy in order to be confident that the machine had worked—but how could you do that? This objection is natural but it’s just another reflection of the ambiguity currently being discussed. I mentioned above that there is a sense in which, upon waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t know whether the machine had worked, and the sceptic is just pointing this out in a different way: “You could be the copy” is just another way of saying, “You don’t know whether the machine worked.”

It doesn’t matter if “you” turn out to be the copy, judging wrongly that the machine had worked, because the ability of your copy to descry his situation is not under scrutiny here. Recall that we were trying to ascertain whether you—the person who entered the machine—would be able to tell that the machine had worked, should you find yourself waking up on Mars. Should the machine fail, you’d die, and your copy would find himself awakening on Mars, but there was never a concern with whether he would (in that event) be able to tell that the machine had failed. What your copy thinks or judges, should he come into being, is irrelevant for our purposes. What matters is only whether you are able to correctly judge that the machine had worked, should you find yourself waking up on Mars.

Your copy, in our context, is essentially an interloper who pilfers your memories and gets into all sorts of trouble because of that. But none of this has to do with you, or your ability to tell that the machine had worked, should you find yourself waking up on Mars.

I find it useful to think of this in terms of an epistemological experiment conducted by God. He creates a world where the machine works and watches you enter the machine and press the button. You thereafter wake up on Mars, whereupon God asks if you can tell whether the machine had worked. Just say, “Yes,” and you will always be right. Even God must acknowledge that you know the answer. (You always get it right.)

To see this, consider what happens if, upon waking up on Mars above, you make the “naive” judgement that the machine had worked, e.g., you just go by the appearances. (“This thing works!” you aver.) Well, the sceptic would retort as before that—hold on a second—your judgement may be incorrect: perhaps the machine actually failed—the original subject having died—and you’re just the copy with false memories of having entered the machine. The sceptic draws attention here to the possibility of your judgement being incorrect, but notice that the person at risk of making this incorrect judgement is not you, the one who entered the machine, but your copy, the one with false memories.

Note. This is obscured by the formulation, “Your judgement may be incorrect,” or “Your memories may be false,” which may suggest that only one person (you) is involved, whereas in fact there are two (you and your copy). Contrast this with a case which genuinely involves one person: imagine having a neurological syndrome that saddles you with false memories from time to time. Here, too, we might have occasion to say, “Are you sure that happened? Your judgement may be incorrect. Your memory may be false.” In this case, it really is your memory that is in question, whereas, in ours, there’s nothing wrong with your memory and it’s only your copy’s memory that is false. (Likewise for your judgement.)

Note. This is obscured by the formulation, “Your judgement may be incorrect,” or “Your memories may be false,” which may suggest that only one person (you) is involved, whereas in fact there are two (you and your copy). Contrast this with a case which genuinely involves one person: imagine having a neurological syndrome that saddles you with false memories from time to time. Here, too, we might have occasion to say, “Are you sure that happened? Your judgement may be incorrect. Your memory may be false.” In this case, it really is your memory that is in question, whereas, in ours, there’s nothing wrong with your memory and it’s only your copy’s memory that is false. (Likewise for your judgement.)

Recall that we were trying to ascertain whether you—the person who entered the machine—would be able to tell that the machine had worked, should you find yourself waking up on Mars. Should the machine fail, you’d die, and your copy would find himself awakening on Mars, but there was never a concern with whether he would (in that event) be able to tell that the machine had failed. What your copy thinks or judges, should he come into being, is irrelevant for our purposes.

Note. In a different context, what your copy thinks or judges may matter: see further below.

Note. In a different context, what your copy thinks or judges may matter: see further below.

So there as you stand with your finger on the button, it should be plain to you that nothing can go wrong: there is no danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) The sceptic contends that if you pressed the button and found yourself waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t really know whether the machine had worked: should you be inclined to think so, you could well be wrong. But there is no such danger of being wrong. (The only person who could be wrong here is your copy.)

So there as you stand with your finger on the button, it should be plain to you that nothing can go wrong: there is no danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) The sceptic contends that if you pressed the button and found yourself waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t really know whether the machine had worked: should you be inclined to think so, you could well be wrong. But there is no such danger of being wrong. (The only person who could be wrong here is your copy.)

You should have no hesitation therefore in judging that the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars. You know in advance that you could never get this judgement wrong, so you may confidently judge that the machine had worked.

The sceptic may retort that you could not reasonably make this judgement unless you knew (upon thus waking) that you were the one who entered the machine. Only the person who entered the machine would get this judgement right; the copy would get it wrong. So you need to rule out that you’re the copy before you can “confidently” make this judgement. But then we’re back to square one. How do you rule out that you’re the copy?

Unfortunately, this is the same confusion. When the sceptic says that you could be the copy, he doesn’t mean you—the person who entered the machine—could be the copy. Obviously, the person who entered the machine couldn’t be the copy: ex hypothesi, they are different persons. The sceptic means rather that it could be your copy who was now waking up on Mars and attempting “confidently” (though erroneously) to judge that the machine had worked. Now, this is certainly true, but we have already seen that it is irrelevant since your copy is not you. It wouldn’t matter if your copy incorrectly judged that the machine had worked, when in fact it had failed. So you don’t have to “rule out” that you’re the copy, any more than you have to “rule out” that your memories are false, or that your judgement that the machine had worked is incorrect. Were any of these possibilities to come true (and they are all of a piece), they would be true of your copy and may safely be ignored.

Unfortunately, this is the same confusion. When the sceptic says that you could be the copy, he doesn’t mean you—the person who entered the machine—could be the copy. Obviously, the person who entered the machine couldn’t be the copy: ex hypothesi, they are different persons. The sceptic means rather that it could be your copy who was now waking up on Mars and attempting “confidently” (though erroneously) to judge that the machine had worked. Now, this is certainly true, but we have already seen that it is irrelevant since your copy is not you. It wouldn’t matter if your copy incorrectly judged that the machine had worked, when in fact it had failed. So you don’t have to “rule out” that you’re the copy, any more than you have to “rule out” that your memories are false, or that your judgement that the machine had worked is incorrect. Were any of these possibilities to come true (and they are all of a piece), they would be true of your copy and may safely be ignored.

An equally confused retort would be that, upon waking up on Mars, you’d just be saying that the machine had worked without really knowing that it had. All you’d really know is that your words would be true if you were real, and irrelevant if you were copy. But you wouldn’t really know if you were real or copy.

This is the same confusion in a different form. There is admittedly a sense in which “you” wouldn’t know if you were real or copy, but it is irrelevant in the same way. In this same sense, “you” wouldn’t know that the machine had worked; “you” could be wrong if you judged that it did; and so on. In each of these formulations, the pronoun “you” potentially refers to either you or your copy, as though one of you were chosen at random and put to the test. There are sceptical contexts in which this formulation would be relevant and natural.

For instance, consider the scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. Can you rule out that this did not just happen? Like our case, either you are who you remember yourself to be—“the real you”—or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past—“the copy”. And, in this case, I agree that there appears to be no saying which one: you just don’t know. Here, it doesn’t matter if you—the subject of the epistemic predicament—happen to be real or copy. Should you hazard a guess as to whether the universe just sprung into being, and you happen to get it wrong, it doesn’t matter if you get it wrong qua being real or copy: it would be just as bad either way. The real and the copy are on a par in this respect: both of them are under the same epistemic obligation to get their “guesses” right. This just has to do with the context in which Russell raises his sceptical scenario. You get no special treatment if you happen to be real, as opposed to copy.

For instance, consider the scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. Can you rule out that this did not just happen? Like our case, either you are who you remember yourself to be—“the real you”—or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past—“the copy”. And, in this case, I agree that there appears to be no saying which one: you just don’t know. Here, it doesn’t matter if you—the subject of the epistemic predicament—happen to be real or copy. Should you hazard a guess as to whether the universe just sprung into being, and you happen to get it wrong, it doesn’t matter if you get it wrong qua being real or copy: it would be just as bad either way. The real and the copy are on a par in this respect: both of them are under the same epistemic obligation to get their “guesses” right. This just has to do with the context in which Russell raises his sceptical scenario. You get no special treatment if you happen to be real, as opposed to copy.

An incorrect judgement on your copy’s part would be your copy’s problem, not yours. For example, if, on the basis of this incorrect judgement, your copy schedules a “return trip,” that would be his undoing, not yours.

What all of this means is that, if you enter the machine, press the button, and find yourself waking up on Mars, the skeptic has nothing on you if you judged that the machine had worked. Your copy might get this judgment wrong should he attempt the parallel judgement upon waking up on Mars, but not you. Indeed, it should be clear anyway that you could never get this judgment wrong. It would be correct solely in virtue of the fact that it was you who was making the judgement.

So there as you stand with your finger on the button, it should be evident to you that nothing can go wrong: there is absolutely no danger of you waking up on Mars and wrongly judging that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) The sceptic would have you believe that, if you found yourself waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t really know whether the machine had worked: should you be inclined to think so, you could very well be wrong. But there is no such danger of being wrong!

It is important to see that there are two distinct people here, one with a genuine memory (you), the other with a false memory (your copy), rather than a single person whose memory may either be genuine or false, as might be inadvertently suggested by the ambiguous formulation, “Your memory might be false.”

In the case with one person, the sceptic’s retort would indeed have a point. Imagine having a neurological syndrome that saddles you with false memories from time to time. Then we might on occasion say to you, “Did that really happen? Your memory might be false.” Here, your memory would genuinely be in question, whereas, in our case, your memory is beyond reproach and it is only your copy’s memory that is false. As mentioned, our case revolves around two people, one of whom remembers correctly, the other wrongly, whereas the neurological case revolves around a single person who sometimes remembers correctly, sometimes wrongly. These cases should not be confused.

More akin to our case is the scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. Can you rule out that this did not just happen? Like our case (and unlike the neurological one), this case revolves around two people: either you are who you remember yourself to be—“the real you”—or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past—“the copy”. And there appears to be no saying which one. Here too we can say, “Your memory might be false,” meaning again, not that the real you might have false memories, but that the person currently in Russell’s predicament might be the copy.

More akin to our case is the scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. Can you rule out that this did not just happen? Like our case (and unlike the neurological one), this case revolves around two people: either you are who you remember yourself to be—“the real you”—or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past—“the copy”. And there appears to be no saying which one. Here too we can say, “Your memory might be false,” meaning again, not that the real you might have false memories, but that the person currently in Russell’s predicament might be the copy.

All of this is exactly as in our case.

But, here too, there is a crucial difference between Russell’s case and ours. In Russell’s case, it doesn’t matter if you—the subject of the epistemic predicament—happen to be real or copy. In particular, should you hazard a guess as to whether the universe just sprung into being, and you happen to get it wrong, it doesn’t matter if you get it wrong qua being real or copy: it would be just as bad either way. The real and the copy are on a par in this respect: both of them are under the same epistemic obligation to get their “guesses” right. This just has to do with the context in which Russell raises his sceptical scenario. There is nothing which favours you being either real or copy, so far as Russell’s predicament itself is concerned.

In a different context, we might care about this, but it is of no consequence where our current question of first-person empirical verification of teletransportation is concerned. (It doesn’t matter if your copy gets it wrong, so long as you get it right.)

Notice that, if you were the copy, it wouldn’t matter if you were wrong, since it is not the copy’s ability to descry his situation that is being scrutinized in our context. We only care about your ability to descry your situation.

---------

Well, let’s start by observing that the sceptic’s admonition, “You might be the copy,” doesn’t mean that the real you—the person who originally entered the machine—might be the copy. That wouldn’t be possible since you and your copy are distinct individuals. What the sceptic means is that the person presently waking up on Mars—the one being admonished (“you”)—might be the copy. In other words, it might be the copy who was now waking up on Mars, and this would mean that the machine had failed, rather than worked.

Likewise, “Your memory of entering the machine might be false,” doesn’t mean that the real you might now be waking up on Mars with a false memory of entering the machine—which again wouldn’t be possible in the context of our story. The sceptic means rather that it might be the copy (with said false memory) who was now waking up on Mars.

The point here is not to confuse our case with a superficially similar one in which your memory really might be in question. Imagine having a neurological syndrome that saddles you with false memories from time to time. Then we might on occasion say to you, “Did that really happen? Your memory might be false.” Here, your memory would genuinely be in question, whereas, in our case, your memory is beyond reproach and it is only your copy’s memory that is false. Our case revolves around two people, one of whom remembers correctly, the other wrongly, whereas the neurological case revolves around a single person who sometimes remembers correctly, sometimes wrongly.

More akin to our case is the scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. Can you rule out that this did not just happen? Like our case (and unlike the neurological one), this case revolves around two people: either you are who you remember yourself to be—“the real you”—or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past—“the copy”. And there appears to be no saying which one. Here too we can say, “Your memory might be false,” meaning again, not that the real you might have false memories, but that the person currently in Russell’s predicament might be the copy.

More akin to our case is the scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. Can you rule out that this did not just happen? Like our case (and unlike the neurological one), this case revolves around two people: either you are who you remember yourself to be—“the real you”—or else a freshly-minted individual with false memories of an unreal past—“the copy”. And there appears to be no saying which one. Here too we can say, “Your memory might be false,” meaning again, not that the real you might have false memories, but that the person currently in Russell’s predicament might be the copy.

Similarly, when Russell says, “You can’t tell whether or not the universe has just sprung into being,” he means that any opinion you dare to venture here would really be no better than a guess. Thus, should you aver that the universe has been around for a while, then you’d be right only if you were real and wrong if you were copy. Conversely, dare you aver (for whatever reason) that the universe did just spring into being, then you’d be right if you were copy and wrong if you were real. Either way, since you can’t tell whether you are real or copy, you can’t tell whether or not the universe has just sprung into being, and no purpose would be served by guessing.

All of this is exactly as in our case.

But there is a crucial difference between Russell’s case and ours. In Russell’s case, it doesn’t matter if you—the subject of the epistemic predicament—happen to be real or copy. In particular, should you hazard a guess as to whether the universe just sprung into being, and you happen to get it wrong, it doesn’t matter if you get it wrong qua being real or copy: it would be just as bad either way. The real and the copy are on a par in this respect: both of them are under the same epistemic obligation to get their “guesses” right. This just has to do with the context in which Russell raises his sceptical scenario. There is nothing which favours you being either real or copy, so far as Russell’s predicament itself is concerned.

suppose for eg that you judged that the machine had worked. In the nature of the case your copy would judge the same, but he would be wrong.

Let me now say that, in Russell’s case, my sympathies do lie with the sceptic: I agree that you can’t tell whether you are real or copy, i.e., whether or not the universe has just sprung into being.

But there is a crucial difference between Russell’s case and ours. When Russell says, “You can’t tell whether your memories are genuine or false,” the pronoun ‘you’ may refer to either you or your copy, depending on who Russell happens to be addressing. Russell is essentially addressing one of you at random, and his words are true just in case this randomized individual is unable to tell whether his memories are genuine or false. If we use a capitalized ‘YOU’ to denote this randomized individual, then, in Russell’s case, YOU can’t tell whether YOUR memories are genuine or false—e.g., over repeated testing, YOU’D do no better than chance in getting the answer right.

But there is a crucial difference between Russell’s case and ours. Russell’s challenge—“Can you tell whether or not the universe has just sprung into being?”—is not directed to you in particular, as opposed to your copy. It doesn’t matter if the person in Russell’s predicament is you or your copy: the claim (to which I’m sympathetic) is that neither of you can tell whether or not the universe has just sprung into being.

In our case, in contrast, the challenge is understood to be specifically directed to you, the one with genuine memories, the person who enters the teletransporter in an attempt to verify if the machine really works. Our question is whether you can tell that the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars. It is irrelevant whether your copy can tell that the machine had failed, should he find himself waking up on Mars: it was no part of our brief to care about that. And so the sceptic’s claim, “You can’t tell whether the machine has worked or failed,” proves to be irrelevant. The claim is true if understood in Russell’s sense, as being directed indifferently to either you or your copy. But

To see this clearly, imagine that you find yourself waking up on Mars and judge confidently that the machine must have worked. The sceptic taps you on the shoulder and reminds you that—hold on—you might be the copy, the implication being that the machine would in that case have failed and your confident judgement would be wrong.

The sceptic means in this way to warn you against rushing to judge that the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars. “You might be the copy,” is the admonition, the point being that, in that case, your (rushed) judgement would be false.

Unfortunately for the sceptic, however, this admonition overlooks that, in the context of our investigation, it doesn’t matter whether the copy makes a correct judgement as to whether the machine had worked or failed. Our concern was only with whether you—the one who entered the machine—would be able to tell that the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars. There was no concern with whether your copy would be able to tell that the machine had failed should he find himself waking up on Mars. In a different context, this might matter, but not in ours.

For example,

Indeed, as you step into the teletransporter and press the button, you might not care about the fate of your copy at all. Suppose, for instance, that the machine fails, your copy wakes up on Mars, and mistakenly thinks that the machine had worked. This might not bode well for him—e.g., he might schedule “another” trip and die as a result—but the thought of this need not bother you at all since ex hypothesi your copy is not you. At any rate, the sceptic cannot reasonably require that you be able to tell that the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars, as well as that your copy be able to tell that the machine had failed should he find himself waking up on Mars, since it is only your ability to descry your situation that is under investigation.

So the sceptic’s cry, “You might be the copy,” is neither here nor there; an appropriate reply would be, “If I were the copy, I would be irrelevant.” But, without this cry, the sceptic has no case against you, e.g., if you confidently judged that the machine had worked upon waking up on Mars. Indeed, notice that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be bound to make a correct judgement if you judged that the machine had worked. It would be correct solely in virtue of the fact that it was you who was making the judgement. Your copy would be wrong if he attempted the parallel judgement, but not you. You could never get this judgement wrong.

So there as you stand with your finger on the button, it should be evident to you that nothing can go wrong: there is absolutely no danger of you waking up on Mars and wrongly judging that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) The sceptic would have you believe that, if you found yourself waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t really know whether the machine had worked: should you be inclined to think so, you could very well be wrong. But there is no such danger of being wrong! Only your copy could get this wrong; but, as before, he is not you.

This looks straightforward at first glance but, to begin to see where it goes wrong, consider an opposing point of view. Consider that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be bound to make a correct judgement if you judged that the machine had worked. Your judgement would be correct even if you couldn’t tell whether your memories were genuine or false. It would be correct just because it was you who was making the judgement. Your copy would be wrong if he attempted the parallel judgement, but not you. You could never get this judgement wrong.

So there as you stand with your finger on the button, it should be plain to you that nothing can go wrong: there is no danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) The sceptic would have you believe that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t really know whether the machine had worked: should you be inclined to think so, you could well be wrong. But, as just explained, there is no such danger of being wrong.

So there as you stand with your finger on the button, it should be plain to you that nothing can go wrong: there is no danger of you waking up on Mars and judging wrongly that the machine had worked when, in fact, it had failed. (There is no danger of you waking up in your copy’s body.) The sceptic would have you believe that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t really know whether the machine had worked: should you be inclined to think so, you could well be wrong. But, as just explained, there is no such danger of being wrong.

The bottom line is that you may confidently judge that the machine had worked should you as much as seem to find yourself waking up on Mars. You know that you could never get this judgement wrong and would therefore have every claim to know that the machine had worked.

The sceptic might retort that you could not reasonably make this judgement unless you knew (upon waking up on Mars) that you were the one who entered the machine. After all, only the person who entered the machine would get this judgement right; the copy would get it wrong. So you need to rule out that you’re the copy before you can “confidently” make this judgement. But then we’re back to square one. How do you rule out that you’re the copy?

The sceptic might retort that you could not reasonably make this judgement unless you knew (upon waking up on Mars) that you were the one who entered the machine. After all, only the person who entered the machine would get this judgement right; the copy would get it wrong. So you need to rule out that you’re the copy before you can “confidently” make this judgement. But then we’re back to square one. How do you rule out that you’re the copy?

Unfortunately, this retort is confused. When the sceptic says that “you” could be the copy, he doesn’t mean you—the person who entered the machine. Obviously, the person who entered the machine couldn’t be the copy: ex hypothesi, they are different persons. What the sceptic means rather is that it could be the copy who is now waking up on Mars and attempting confidently (though erroneously) to judge that the machine had worked. Now, this may well be true, but it is also irrelevant, since this person would not be you. As mentioned previously, you could never get this judgement wrong; only your copy could.

To see what’s going on here, it helps to consider a similar scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. Can you rule out that this did not just happen? Like our case, this one revolves around two people: either you are who you remember yourself to be (the genuine article) or else a freshly-created individual with false memories of an unreal past (the copy). And there appears to be no telling which one. In this case, my sympathies lie with the sceptic: you simply cannot tell whether you are real or copy, i.e., whether or not the universe has just materialized.

To see what’s going on here, it helps to consider a similar scenario once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world suddenly springs into being with everyone having false memories of an unreal past. Can you rule out that this did not just happen? Like our case, this one revolves around two people: either you are who you remember yourself to be (the genuine article) or else a freshly-created individual with false memories of an unreal past (the copy). And there appears to be no telling which one. In this case, my sympathies lie with the sceptic: you simply cannot tell whether you are real or copy, i.e., whether or not the universe has just materialized.

This case is usefully compared with ours because it may seem on the surface to be the same sort of case. Just as you cannot tell in Russell’s case whether or not the universe has just materialized, you cannot tell upon waking up on Mars whether or not the machine had worked. In either case, you may be real or copy and you just cannot tell.

But there is a crucial difference between Russell’s case and ours. In Russell’s case, it doesn’t matter whether the subject of the epistemic predicament happens to be the real person or the copy: either way, the subject is being held to account for what he or she may claim to know. Suppose, for instance, that you consider Russell’s scenario absurd and contend that you are obviously real. The retort would be that, for all that you can tell, you are the copy, in which case your contention would be wrong. Notice in this way how the copy is potentially being held to account no less than the real person is. It doesn’t matter if you are real or copy: you are required either way to be right.

In our case, however, only the real person is being held to account. We were trying to ascertain whether you—the person who entered the machine—could tell that the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars. There is no concern with whether your copy could tell that the machine had failed should he find himself waking up on Mars. In a different context, we might care about this, but it is of no consequence where our current question of first-person empirical verification of teletransportation is concerned: it doesn’t matter if your copy gets it wrong, so long as you get it right. An example of a different context is given in Dennett’s tale above, in which it doesn’t matter if the protagonist is real or copy: she wants to be right either way.

Accordingly, if you find yourself waking up on Mars and contend that the machine had worked, the sceptic can no longer retort, as in Russell’s case, that, for all that you can tell, you might be the copy and that your contention might be false. If you were the copy, it wouldn’t matter that your contention was false because the copy is not being held to account.

The bottom line, therefore, is that you may enter the machine, press the button, and simply resolve to judge that the machine had worked should you so much as seem to find yourself waking up on Mars. You could never get this judgement wrong and would have every claim upon so waking to know that the machine had worked. Your copy, should he come into existence, would erroneously make the same judgement, but this has got nothing to do with you. Indeed, simultaneously as your copy makes this wrong judgement, you could well be making the correct judgement that the machine had failed, e.g., by finding yourself waking up in purgatory. In testing the machine, we want you to be able to tell whether the machine had worked or failed. This refers to A and B below, as opposed to A and C, which is what the sceptic has erroneously focused on.

In our case, in contrast, we care primarily about you (lower case), the one with genuine memories, the person who enters the teletransporter in an attempt to verify if the machine really works. Our question is whether you can tell whether the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars. It is irrelevant whether your copy can tell, should he find himself waking up on Mars: it was no part of our brief to care about that. And so the sceptic’s claim, “You can’t tell whether your memories are genuine or false,” needs to be handled here with care because it may well be true that YOU can’t tell whether YOUR memories are genuine or false, without it being true that you can’t tell whether your memories are genuine or false.

In my opinion, the sceptic stumbles in failing to heed this difference. It’s not true that you—the person who entered the machine—can’t tell whether your memories are genuine, should you find yourself waking up on Mars. (Likewise, whether the machine had worked, whether you were the one who entered the machine, etc.) As explained above, if you go simply by “how it seems,” you’re bound to get the answer right. By any measure, you would be able to tell. Tested repeatedly, for instance, you’d always give the correct answer and there’d be no grounds whatever for saying that you couldn’t tell, or didn’t know. This strategy of going by how it seems doesn’t work in Russell’s case because it is implicitly required there that the correct answer be given by the person selected at random between you and your copy. In contrast, it is part of the nature of our case that it doesn’t matter what answer your copy gives and that the correct answer only be given by you. The person being addressed in our case is you, specifically, as opposed to the one selected at random between you and your copy.

In this case, you do need to know whether you are real or copy, because it is required that you get the answer right either way.

In our case, by contrast, what the copy ends up judging, should he find himself waking up on Mars, is unimportant. The requirement is only that the person who entered the machine—you—have good grounds to judge that the machine had worked. According to the sceptic, you cannot have such grounds unless you know that you are the person who entered the machine. Now it is true that, in the sense in which the sceptic intends it, you don’t know whether you are the person who entered the machine. But, as just explained, it does not follow that you have to know this in order to have good grounds for judging that the machine had worked. Indeed, given that you cannot get this judgement wrong, you have all the grounds that you need for making it. In this same sense, you also do know that you are the person who entered the machine. You know this in the sense that, knowing that if you so judge as much, you could never get it wrong, you should have no hesitation in judging as much.

but this time it literally is your memory that is in question. In our case, in contrast, despite the same sceptical form of words being used—“You can’t tell if your memory is genuine or false”—your memory is never at fault.

There is a sense in which the danger in question exists but it goes beyond our original concern. Our concern was with whether the person who entered the machine, supposing he woke up on Mars, would know whether the machine had worked or failed. Another concern might be whether this person’s copy (should he come into existence) would know. When the sceptic says that if you woke up on Mars, you would not know whether the machine had worked or failed, the pronoun ‘you’ refers indifferently to either you or your copy, as though God had picked one of “you” at random and asked, ‘Did the machine work or fail?’ This randomly picked subject would do no better than chance in answering the question. This is the sense in which “you” don’t know whether the machine had worked or failed.

But it was no part of our brief to care whether your copy gets the answer right. Our concern was only with whether you, the one who entered the machine, do.

Why does the sceptic think there is such a danger? Well, he claims that if you entered the machine, pressed the button, and found yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon so waking) whether your memory of having entered the machine was genuine or false. You wouldn’t know if you were the one who originally entered the machine, or just a freshly-minted copy with false memories of having done so. As such, you’d be unable to tell if the machine had worked or failed. (If you happened to be the copy, the machine would in fact have failed.)

re is another sort of case where there is such a danger, with which ours is easily confused. Suppose you had a neurological syndrome (say) that saddled you with false memories from time to time. In some given instance of this case,

we can likewise say, “You don’t really know if your memory is genuine or fake,” but this time it really is your memory that is in question and the corresponding scepticism concerning your past really does have a bite. But our case is not of this sort.

Why could you not just resolve to judge that the machine had worked if, upon pressing the button, you found (or seemed to find) yourself waking up on Mars?

I will argue that these simple facts constitute a basis for resisting the sceptical provocation. Very roughly, knowing these facts as you press the button, you can simply resolve to judge that the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars. Not only would your judgement be bound to be correct, it would also be well-founded, and so you could claim, upon so waking and following up on the resolution, to know that the machine had worked.

The sceptic claims that, upon waking up on Mars, you would not be able to tell that the machine had worked. There is a sense in which this is true, as I will make clear below, but the fact that your judgement that the machine had worked could never be wrong suggests also that there may be another sense in which you would so be able to tell. After all, if you could never get the judgement wrong, why should you hesitate in judging that the machine had worked should you find yourself waking up on Mars? I will argue that this line of thinking is sound and is more relevant for our purposes.

To this line of thinking, the sceptic would naturally retort that, upon waking up on Mars, you wouldn’t know whether it was you or your copy who was waking up, and that this is what generates the sceptical threat. You need to know that it was you—the one who entered the machine—that was waking up, otherwise you’d have no grounds to conclude that “your” memories were genuine and that the machine had worked.

This retort would have a point if it were required quite generally that the person waking up on Mars (whether he be real or copy) be able to tell whether the machine had worked or failed. But this is not required. It is not required that your copy be able to tell that the machine had failed, but only that you be able to tell that the machine had worked.

So our case differs from a superficially-similar case once mentioned by Russell in which the entire world sprang into being a moment ago with everyone having false memories of an unreal past: how can you tell whether or not this happened? In this case, you do need to know whether you are real or copy, because it is required that you get the answer right either way.