Seeing and being

Preface

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

5. What is knowing?

If seeing is just knowing, then all that “goes on” when I look at a tree is that I come to know that a tree (of a certain shape, size and colour, etc.) stands before me.

If this is right, then we simply have to figure out what “knowing” is in order to understand what “seeing” is. But this is not very easy. What, after all, is our conception of “knowing”? What is it for someone to know that a tree stands before him, or that things are thus and so, or that the world is a certain way? This question seems no easier than the one we started with – What is seeing? – and there is no prospect this time of passing the buck.

Before trying to make headway with this, it may help to step back a little and make a few observations.

First, the concept of “knowing” above is not meant to be opposed to the concept of “believing.” (Someone like Armstrong, who holds that seeing is believing rather than knowing, is an ally, not an adversary.) Rather, the difference between “knowing” and “believing” is not particularly significant at this stage, given our focus on paradigm cases of seeing. Indeed, the difference is negligible compared to the weight of the proposal that seeing is just knowing/believing, and I will sometimes express this by saying that, according to the proposal, to see is just to take the world to be a certain way, where “take” is neutral between “know” and “believe.” The bottom line is that our question above, ‘What is knowing?,’ is not significantly different from the question, ‘What is believing?’ At least, the difference will not matter much for now and our answer may slide over it as well.

At least, the difference will not matter much for now and our answer may slide over it as well.

I mention this because a traditional account of knowledge – going back to Socrates – is that knowledge is justified true belief, but this sort of answer to the question, ‘What is knowing?,’ is of no interest to us, for the reason just given. We need an answer, rather, that plays down the difference between knowing and believing.

Notice next that, if this is what it comes down to, then some philosophers will say that our difficulties are essentially solved, because, according to them, we have a decent enough grasp of the phenomenon of believing, or knowing, or otherwise taking something to be true. What these philosophers have in mind is the notion of a physical “representation” in one’s brain of one’s surroundings. On this view, a specific structure within a subject’s brain – like a bunch of neurons, or the connections between them, or even a stable, dynamic process within these connections – may be considered to be a “sign” or “mark” that the world is a certain way, particularly if this structure was caused to come into existence in a suitable way and causes the subject thereafter to react (or behave) in appropriate ways. For many philosophers, this is essentially what it is for a subject to know, or believe, or take the world to be a certain way – the subject simply has a suitable “representation” that the world is that way, in his or her brain.

In this sense, even a machine can know various things about the world, as when a chess computer “knows” that the queens are off the board or that white has the better position – it has suitable “representations” of these facts within its electronic brain. Needless to say, this representational conception of one’s “awareness” of the world has been the key to the construction of such intelligent and purposeful machines. Indeed, for someone like Armstrong, this is part of the point of championing the view that seeing is just knowing (or believing) – it enables us to reduce one problematic phenomenon (seeing) to another that we feel we understand better (knowing/believing).

This is not my reason for championing the view, however, and this is also the point where we must remember that it is the plain man’s conception of seeing that we are ultimately trying to unravel. If this “reduces” to the concept of knowing (believing, taking), then it is the plain man’s conception of these notions that we want to elucidate – but it is wildly unclear that we can attribute the “representational” conceptions of these notions to the plain man.

The notion of “knowing,” for example, is undeniably a part of our daily conceptual apparatus. Even young children demonstrate a grasp of the notion when they look under a bed (say) to “find out” what is there. At an early age, children understand that some things are known to them while others are unknown and that there is such a thing as being curious. They also grasp that what one person knows may be unknown to another, as when they play hide and seek – and so on. The concept of “knowing” something is fairly fundamental and it is acquired – however inchoately – at an early age. But what does the phenomenon really amount to, for the average man? What is his conception of it?

I think one thing is clear. When the plain man thinks of himself as “knowing” something, he does not think of himself as having a representation in his head, as though a fact was somehow recorded in his brain. This is already clear for the child who looks under her bed and “finds” her lost toy there – a child would hardly possess the concept of a “representation” in her head. But it is also clear for the average adult who knows (say) when the next train is arriving. He doesn’t think of this piece of knowledge as some configuration of his brain, or as some “inner state” of his body, apt to cause him to behave in certain ways. Our everyday concept of knowing is much more visceral than that. To the man on the street, knowing is predominantly a “first-personal” affair involving a “conscious self” – a someone – who knows.

Consider our chess computer again, which “knows” that the queens are off the board. The average man might well suggest that the computer doesn’t really know anything because there’s nobody there to do any knowing. Talk of the computer “knowing” is just a manner of speaking, or an anthropomorphism, since the computer doesn’t have anything like a “first-person” viewpoint on things. In this respect, the plain man’s conception of knowing is very much like his conception of seeing – he would not regard a security camera as “seeing” anything for exactly the same reason.

This doesn’t tell us what the plain man’s concept of knowing is, but it does illustrate how distant the representational conception of knowing is from the plain man’s notion. As normally propounded, the representational conception doesn’t require the existence of a “conscious self” with a “first-person” point of view, and its proponents (accordingly) often have no qualms in speaking of machines or plants as knowing things, or as having beliefs. John Searle relates the following exchange with the cognitive scientist John McCarthy:

What then do we ordinarily mean when we speak of someone “knowing” something? As mentioned, I think that this is the crux of the matter. The phenomenon of seeing baffles us, it seems to me, because it is the underlying phenomenon of knowing that really baffles us, and not because of any perplexing feature peculiar to seeing alone. We can get a sense of this if we think a little more ingenuously about both knowing and seeing. Knowing is clearly a phenomenon of greater scope than seeing. You can normally see only what’s currently before you but you can know all sorts of things that are far removed in space and time. This is like having a crystal ball in your head but we are so used to it that we hardly pause to consider what could possibly be involved here. What is it that happens when someone “reaches out and grasps” that dinosaurs used to roam the earth or that a bright, blue train will pull into the station within the next hour? What is this “grasping” of some bit of the world – almost any bit in principle – that we manage to effect all the time? (Seeing is just a special case with a restricted scope.)

If you reflect on a simple case of yourself knowing something – e.g., that the blue train is arriving soon – then what this comes down to, putting it dramatically to begin with, is that the state of affairs in question becomes “real for you.” The pending train becomes a “part of your world,” or is otherwise “incorporated into your reality.” Your world “expands” when you learn something new, whereas ignorance is a “gap” in your reality. I think that we all recognize some such sentiments as being a part of the “phenomenology” of knowing.

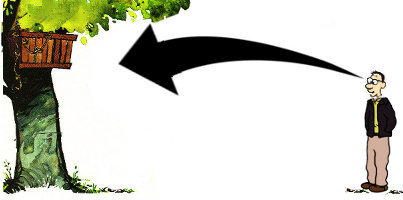

Following Brentano and Husserl, philosophers often speak of the intentionality of mind as the mind’s capacity to “embrace” reality, and this is essentially the same phenomenon. When you know something, what you know is “incorporated into your reality,” as dramatized above. Alternatively, some philosophers speak of your mind being “directed” upon the relevant bit of reality, or being “about” that bit of reality, as in one of our previous cartoons:

There are many metaphors to choose from, and some of them may be better than the others, but the exact choice of metaphor is not as important as our visceral grasp of the phenomenon. We are all familiar with the phenomenon of knowing something and can “engage” with it (in our own case) at any time. The challenge is to describe the phenomenon, or otherwise pin it down, in a way that dispenses with the metaphor and the drama. What, in plain terms, do we really take to be “going on” when we know something?

In trying to answer this question, the essential thing is not to lose sight of the pre-theoretic phenomenon. This is all too easy to do, as Valberg reminds us in the following passage. This passage concerns visual experience, or seeing, but it may just as well concern the phenomenon of knowing:

And so we need a “totally different conception” of experience (or of knowing) – one that is more recognizable to the plain man. But what will it be? Valberg does sketch one for our consideration and it will be useful to examine it briefly as a second example – our first was Ryle’s – of the kind of lateral thinking that is needed here. According to Valberg, it makes better sense to conceive of experience as a “horizon” within which some bit of the world may “present itself”:

The metaphor of a “horizon” as applied to either seeing or knowing is nevertheless very suggestive, and I do think that there may be something in it – but we really do need to get past the metaphors. In the sections that follow, I will suggest a relatively novel account of both knowing and seeing that attempts to do just this. I will try, above all, to do justice to the plain man’s conceptions of these phenomena, including the thought – which I continue to attribute to him – that seeing is just a variety of knowing.

I remarked above that the phenomenon of seeing baffles us because it is the underlying phenomenon of knowing that really baffles us, and not because of any perplexing feature peculiar to seeing alone. This is usefully contrasted with the approach of many contemporary philosophers who tend to hold that “psychological” mental states like knowing, believing and taking are not all that hard to understand, unlike “phenomenal” mental states like seeing, hearing, and feeling, which raise “hard problems.” David Chalmers puts it this way:

At some point, one has to dig one’s heels in and call it as one sees it and this is the right point for me. And so I will henceforth assume without further apology that, where the plain man is concerned, seeing is just a case of knowing, so that we can plunge right into the difficult question of what we should make of the plain man’s concept of knowing. We have barely made a dent in this above but this is the really “hard” question, so far as I can see.

If seeing is just knowing, then all that “goes on” when I look at a tree is that I come to know that a tree (of a certain shape, size and colour, etc.) stands before me.

If this is right, then we simply have to figure out what “knowing” is in order to understand what “seeing” is. But this is not very easy. What, after all, is our conception of “knowing”? What is it for someone to know that a tree stands before him, or that things are thus and so, or that the world is a certain way? This question seems no easier than the one we started with – What is seeing? – and there is no prospect this time of passing the buck.

Before trying to make headway with this, it may help to step back a little and make a few observations.

First, the concept of “knowing” above is not meant to be opposed to the concept of “believing.” (Someone like Armstrong, who holds that seeing is believing rather than knowing, is an ally, not an adversary.) Rather, the difference between “knowing” and “believing” is not particularly significant at this stage, given our focus on paradigm cases of seeing. Indeed, the difference is negligible compared to the weight of the proposal that seeing is just knowing/believing, and I will sometimes express this by saying that, according to the proposal, to see is just to take the world to be a certain way, where “take” is neutral between “know” and “believe.” The bottom line is that our question above, ‘What is knowing?,’ is not significantly different from the question, ‘What is believing?’

I mention this because a traditional account of knowledge – going back to Socrates – is that knowledge is justified true belief, but this sort of answer to the question, ‘What is knowing?,’ is of no interest to us, for the reason just given. We need an answer, rather, that plays down the difference between knowing and believing.

Notice next that, if this is what it comes down to, then some philosophers will say that our difficulties are essentially solved, because, according to them, we have a decent enough grasp of the phenomenon of believing, or knowing, or otherwise taking something to be true. What these philosophers have in mind is the notion of a physical “representation” in one’s brain of one’s surroundings. On this view, a specific structure within a subject’s brain – like a bunch of neurons, or the connections between them, or even a stable, dynamic process within these connections – may be considered to be a “sign” or “mark” that the world is a certain way, particularly if this structure was caused to come into existence in a suitable way and causes the subject thereafter to react (or behave) in appropriate ways. For many philosophers, this is essentially what it is for a subject to know, or believe, or take the world to be a certain way – the subject simply has a suitable “representation” that the world is that way, in his or her brain.

In this sense, even a machine can know various things about the world, as when a chess computer “knows” that the queens are off the board or that white has the better position – it has suitable “representations” of these facts within its electronic brain. Needless to say, this representational conception of one’s “awareness” of the world has been the key to the construction of such intelligent and purposeful machines. Indeed, for someone like Armstrong, this is part of the point of championing the view that seeing is just knowing (or believing) – it enables us to reduce one problematic phenomenon (seeing) to another that we feel we understand better (knowing/believing).

This is not my reason for championing the view, however, and this is also the point where we must remember that it is the plain man’s conception of seeing that we are ultimately trying to unravel. If this “reduces” to the concept of knowing (believing, taking), then it is the plain man’s conception of these notions that we want to elucidate – but it is wildly unclear that we can attribute the “representational” conceptions of these notions to the plain man.

The notion of “knowing,” for example, is undeniably a part of our daily conceptual apparatus. Even young children demonstrate a grasp of the notion when they look under a bed (say) to “find out” what is there. At an early age, children understand that some things are known to them while others are unknown and that there is such a thing as being curious. They also grasp that what one person knows may be unknown to another, as when they play hide and seek – and so on. The concept of “knowing” something is fairly fundamental and it is acquired – however inchoately – at an early age. But what does the phenomenon really amount to, for the average man? What is his conception of it?

I think one thing is clear. When the plain man thinks of himself as “knowing” something, he does not think of himself as having a representation in his head, as though a fact was somehow recorded in his brain. This is already clear for the child who looks under her bed and “finds” her lost toy there – a child would hardly possess the concept of a “representation” in her head. But it is also clear for the average adult who knows (say) when the next train is arriving. He doesn’t think of this piece of knowledge as some configuration of his brain, or as some “inner state” of his body, apt to cause him to behave in certain ways. Our everyday concept of knowing is much more visceral than that. To the man on the street, knowing is predominantly a “first-personal” affair involving a “conscious self” – a someone – who knows.

Consider our chess computer again, which “knows” that the queens are off the board. The average man might well suggest that the computer doesn’t really know anything because there’s nobody there to do any knowing. Talk of the computer “knowing” is just a manner of speaking, or an anthropomorphism, since the computer doesn’t have anything like a “first-person” viewpoint on things. In this respect, the plain man’s conception of knowing is very much like his conception of seeing – he would not regard a security camera as “seeing” anything for exactly the same reason.

This doesn’t tell us what the plain man’s concept of knowing is, but it does illustrate how distant the representational conception of knowing is from the plain man’s notion. As normally propounded, the representational conception doesn’t require the existence of a “conscious self” with a “first-person” point of view, and its proponents (accordingly) often have no qualms in speaking of machines or plants as knowing things, or as having beliefs. John Searle relates the following exchange with the cognitive scientist John McCarthy:

That this strikes us as funny shows how far removed this way of thinking is from our own and Searle is right to emphasize this. The representational conception of knowing is clearly valid in its own right and is no doubt related to our everyday concept of knowing. Most obviously, when, in the everyday sense, you know some fact about the world, then it seems likely that there is some representation in your brain of the fact that you know. But that there is some such representation is not what we ordinarily mean when we speak of knowing something, any more than that there is neural activity in the visual cortex is what we ordinarily mean when we speak of seeing something.McCarthy says even ‘machines as simple as thermostats can be said to have beliefs.’ And indeed, according to him, almost any machine capable of problem-solving can be said to have beliefs. I admire McCarthy’s courage. I once asked him: ‘What beliefs does your thermostat have?’ And he said: ‘My thermostat has three beliefs – it’s too hot in here, it’s too cold in here, and it’s just right in here.’ (Minds, Brains and Science, p. 30.)

What then do we ordinarily mean when we speak of someone “knowing” something? As mentioned, I think that this is the crux of the matter. The phenomenon of seeing baffles us, it seems to me, because it is the underlying phenomenon of knowing that really baffles us, and not because of any perplexing feature peculiar to seeing alone. We can get a sense of this if we think a little more ingenuously about both knowing and seeing. Knowing is clearly a phenomenon of greater scope than seeing. You can normally see only what’s currently before you but you can know all sorts of things that are far removed in space and time. This is like having a crystal ball in your head but we are so used to it that we hardly pause to consider what could possibly be involved here. What is it that happens when someone “reaches out and grasps” that dinosaurs used to roam the earth or that a bright, blue train will pull into the station within the next hour? What is this “grasping” of some bit of the world – almost any bit in principle – that we manage to effect all the time? (Seeing is just a special case with a restricted scope.)

If you reflect on a simple case of yourself knowing something – e.g., that the blue train is arriving soon – then what this comes down to, putting it dramatically to begin with, is that the state of affairs in question becomes “real for you.” The pending train becomes a “part of your world,” or is otherwise “incorporated into your reality.” Your world “expands” when you learn something new, whereas ignorance is a “gap” in your reality. I think that we all recognize some such sentiments as being a part of the “phenomenology” of knowing.

Following Brentano and Husserl, philosophers often speak of the intentionality of mind as the mind’s capacity to “embrace” reality, and this is essentially the same phenomenon. When you know something, what you know is “incorporated into your reality,” as dramatized above. Alternatively, some philosophers speak of your mind being “directed” upon the relevant bit of reality, or being “about” that bit of reality, as in one of our previous cartoons:

There are many metaphors to choose from, and some of them may be better than the others, but the exact choice of metaphor is not as important as our visceral grasp of the phenomenon. We are all familiar with the phenomenon of knowing something and can “engage” with it (in our own case) at any time. The challenge is to describe the phenomenon, or otherwise pin it down, in a way that dispenses with the metaphor and the drama. What, in plain terms, do we really take to be “going on” when we know something?

In trying to answer this question, the essential thing is not to lose sight of the pre-theoretic phenomenon. This is all too easy to do, as Valberg reminds us in the following passage. This passage concerns visual experience, or seeing, but it may just as well concern the phenomenon of knowing:

Valberg’s point is that we often pay lip service to the phenomenon of intentionality. Intentionality is not simply the “aboutness” or “directedness” of a mental state upon reality, as though anything that fits these descriptions will do. These metaphors are meant rather to capture our pre-theoretic grasp of the “world’s presence in experience,” as Valberg puts it. To conceive of experience merely as a “series of states on the part of the subject” with “causal connections” to the world is to lose sight of what is palpable to the plain man, and thus to miss the phenomenon of experience altogether. And, although Valberg does not say this, nor generally discuss the relation between seeing and knowing, I would level exactly the same charge upon the “representational” conception of knowing – it too largely misses the “intentionality” of knowing, as this is pre-theoretically manifest to the man on the street.We unthinkingly start with the conception of experience as a process or series of states on the part of the subject. We then sense (correctly) that such a conception does not allow for the fact of the world’s presence in experience. In order to remedy the deficiency, we confer on the relevant process, etc., the property of being ‘directed (pointed, aimed)’ at the world. Of course we are then saddled with the problem of how to explain this property (the ‘problem of intentionality’). But, however we explain it, we never quite get what we want: the presence of the world. To get that, we have to start in a totally different place, with a totally different conception of experience. (The Puzzle of Experience, pp. 141–2.)

And so we need a “totally different conception” of experience (or of knowing) – one that is more recognizable to the plain man. But what will it be? Valberg does sketch one for our consideration and it will be useful to examine it briefly as a second example – our first was Ryle’s – of the kind of lateral thinking that is needed here. According to Valberg, it makes better sense to conceive of experience as a “horizon” within which some bit of the world may “present itself”:

This conception of experience as a “horizon” accords with an early suggestion of Wittgenstein’s that the self is a “limit” of the world, as Valberg proceeds to explain:Each of us has the idea of a horizon within which the world is present, and which is ‘mine.’ The world is present within the horizon, but since the horizon is nothing in itself, we cannot include it (it?) in the world. I am not saying (of course) that in everyday life this is always, or generally, what we mean by the words ‘(my) experience.’ But, even if we never articulate it, the conception of such a horizon is with us all the time, in the same way that the idea of our own death is with us all the time. (Indeed, the idea of our own death is the idea of there no longer being the horizon.) I shall call this conception of experience the horizonal conception of experience. (Ibid., p. 124.)

The main feature of this alternative conception is that an experience – e.g., a visual experience – is not an event, or state, or process, that takes place (or occurs) anywhere in the world, let alone in our heads. As Valberg puts it, experience is nothing in itself, but is merely something “within which” the world – or a part of it – can be “present.” This is the point of the metaphor of a horizon. (Notice that a conception of this sort accommodates the “diaphanousness” of seeing from the start.) As it stands, however, this alternative conception cannot be said to be completely clear, and Valberg never really unpacks the metaphor to any significant degree. A similar “horizonal” metaphor could probably also be attempted for the phenomenon of knowing – this would actually be quite natural – but I will not pursue this here as Valberg gives us very little to work with.Wittgenstein, in the Tractatus, says that the subject—that is, ‘the metaphysical subject’—is niether the body nor the soul (5.631, 5.5421). The body and the soul are part of the world. But the metaphysical subject, he says, is not part of the world; it is a ‘limit’ of the world (5.632–3). ‘If I wrote a book called The World as I found it, I should have to include a report on my body ... this being a method of isolating the subject, or rather of showing that in an important sense there is no subject; for it alone could not be mentioned in that book’ (5.631).Wittgenstein’s conception of a ‘limit’ of the world, the metaphysical subject, is, I think, very close to the conception of experience that we are trying to catch hold of here: the conception of an experiential horizon. (Ibid.)

The metaphor of a “horizon” as applied to either seeing or knowing is nevertheless very suggestive, and I do think that there may be something in it – but we really do need to get past the metaphors. In the sections that follow, I will suggest a relatively novel account of both knowing and seeing that attempts to do just this. I will try, above all, to do justice to the plain man’s conceptions of these phenomena, including the thought – which I continue to attribute to him – that seeing is just a variety of knowing.

I remarked above that the phenomenon of seeing baffles us because it is the underlying phenomenon of knowing that really baffles us, and not because of any perplexing feature peculiar to seeing alone. This is usefully contrasted with the approach of many contemporary philosophers who tend to hold that “psychological” mental states like knowing, believing and taking are not all that hard to understand, unlike “phenomenal” mental states like seeing, hearing, and feeling, which raise “hard problems.” David Chalmers puts it this way:

It is evident from this passage that Chalmers endorses the representational conception of believing (or knowing) along with the view that seeing involves something like the occurrence of “colour sensations” in the mind, or brain, or head. If you uphold anything like this combination of views, then the suggestion that seeing is a case of knowing will indeed seem rather misguided. It seems to me, however, that neither of these conceptions would be recognizable to the plain man – e.g., our ancient Egyptian – and that their combination is therefore doubly unhelpful for our purposes.[A] belief that it is raining might very roughly be analyzed as the sort of state that tends to be produced when it is raining, that leads to behaviour that would be appropriate if it were raining, that interacts inferentially with other beliefs and desires in a certain sort of way, and so on. There is a lot of room for working out the deails, but many have found the overall idea to be on the right track ...[But] when we wonder whether somebody is having a color experience, we are not wondering whether they are receiving environmental stimulation and processing it in a certain way. We are wondering whether they are experiencing a color sensation, and this is a distinct question ...There is no great mystery about how a state might play some causal role, although there are certainly technical problems there for science. What is mysterious is why that state should feel like something; why it should have a phenomenal quality. (The Conscious Mind, p. 15.)

At some point, one has to dig one’s heels in and call it as one sees it and this is the right point for me. And so I will henceforth assume without further apology that, where the plain man is concerned, seeing is just a case of knowing, so that we can plunge right into the difficult question of what we should make of the plain man’s concept of knowing. We have barely made a dent in this above but this is the really “hard” question, so far as I can see.

Menu

What’s a logical paradox?

What’s a logical paradox? Achilles & the tortoise

Achilles & the tortoise The surprise exam

The surprise exam Newcomb’s problem

Newcomb’s problem Newcomb’s problem (sassy version)

Newcomb’s problem (sassy version) Seeing and being

Seeing and being Logic test!

Logic test! Philosophers say the strangest things

Philosophers say the strangest things Favourite puzzles

Favourite puzzles Books on consciousness

Books on consciousness Philosophy videos

Philosophy videos Phinteresting

Phinteresting Philosopher biographies

Philosopher biographies Philosopher birthdays

Philosopher birthdays Draft

Draftbarang 2009-2024  wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine