Seeing and being

Preface

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

2. What on earth is seeing?

We are trying to spell out or otherwise uncover our everyday concept of seeing – the plain man’s concept. It is common knowledge that we see what’s around us, that we see with our eyes, and that we need light to see. But what is our broad conception of the phenomenon? What do we broadly imagine is “taking place” when someone sees?

Consider a man looking at a tree and let us agree that he sees the tree. We have no trouble identifying either the man or the tree, but it is much harder to pin down the “seeing” that is supposed to be occurring here. There is certainly nothing in the picture that we can point to. Nor would adding more detail to the picture help.

Of course, in seeing the tree, the man is not doing anything to the tree. Seeing a tree is not like pruning a tree, so we cannot expect to observe some specific physical action (of the man) directed upon the tree. But what then do we take to be “going on” when we speak of the man seeing the tree? We seem to have no difficulty understanding such talk in practice.

Some people – for whatever reason (see a bit later) – think of seeing as the emergence of a “private bubble of consciousness” on the part of the subject doing the seeing.

The bubble is sometimes located within the subject’s head, but the essential idea is that the contents of the bubble should be “private” to the subject. —The bubble is in his mind, as it were. Of course, the contents of the bubble are supposed – in some sense – to “reflect” the scene around the subject, but the subject’s vision is nevertheless “confined” within the bubble, as the picture unabashedly suggests.

I do not believe that the man on the street supposes any such thing to be going on when he sees. The main reason is that the bubble creates a “barrier” between a subject and the world, whereas, to the plain man, seeing is more like touching, in the sense of being a “direct communion” with the objects around him. In the language of philosophers, seeing is normally supposed to be a diaphanous phenomenon.

This does not mean that the conception above is incorrect. The point is only that it is not attributable to the ordinary man. That is not how the ordinary man thinks of seeing, whether or not it is a correct way of thinking about seeing. (I don’t imagine it can be correct though.)

A related idea is that seeing is the displaying of an image on a screen in the subject’s mind, as though someone was watching television.

This idea is no better than the previous one. No ordinary person thinks of seeing as the displaying of an image on a screen (of any sort). As mentioned, ordinary people accept that they are in “direct visual contact” with what they see.

Besides, even if there was an image on a screen, we would still have to account for the “seeing” of the image, which was precisely the sort of problem we were struggling with. So the introduction of the screen serves no real purpose.

What then is the plain man’s conception of seeing, if not anything like the above? Articulating it seems so hard that one feels simply like drawing an arrow and proclaiming that seeing is just the “directedness” of the man’s attention upon the tree.

Needless to say, this verges on desperation. Nothing like an arrow actually emerges from the man’s eyes nor does anyone suppose as much. And while the man’s attention is doubtless directed upon the tree, pointing this out is no clearer than saying simply that he sees the tree. So this account is not much better than waving one’s hands before one’s eyes in order to explain the concept of seeing.

Our question is what the plain man takes to be “going on” when he sees something. In attempting to answer this question, remember that there is no point giving the scientific account of what is going on – the one involving photons striking the retina and signals being sent to the visual cortex.

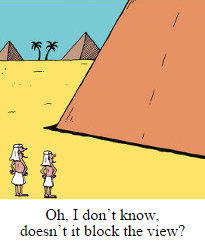

The answer must rather be one that could have been offered by an ancient Egyptian (say), long before anything was known about photons or the function of the brain.

The answer must rather be one that could have been offered by an ancient Egyptian (say), long before anything was known about photons or the function of the brain.

An ancient Egyptian would certainly have had the concept of seeing and could very well have asked himself what his concept of it was. This would be the same question that we are asking ourselves right now, and we would expect it to be answered in the same way. The answer clearly will not refer to anything like photons or the brain.

I mentioned above that our current difficulty is just an instance of the more general difficulty of explaining what consciousness is supposed to be. (Visual consciousness – or seeing – is just a special case.) We accept that we are “conscious” creatures – e.g., I am conscious right now of numerous things transpiring around me – but it is no less hard to explain what we take this phenomenon of “consciousness” to be.

Many philosophers readily admit a difficulty here. David Chalmers says:

Consider our man again, who sees the tree.

If pressed to explain what is “going on” with the man when he sees the tree, we might eventually venture that the same sort of thing “goes on” with him as does with us when we see the tree, and we roughly know what this is from personal experience.

Let’s explore this a bit and see if anything comes out of it. Where seeing is concerned, what is it that we know from personal experience?

When we consider our personal experience of seeing in order to get a handle on the concept, we can easily find ourselves moving around in circles:

In frustration, we feel like raising our hands aloft and declaring, “This is seeing!”

Some people are indeed satisfied with this! Conceding that they can’t explain what it is that they know from their “personal experience” of seeing, they feel that they nevertheless know what they are talking about when they talk about seeing.

My own feeling is that this is not good enough. If you take this “practical grasp” of seeing – as we might call it – and go on to ask how this thing – the “seeing” that we know from personal experience – arises from activity in the brain, you run quickly into a dead end. No one has the slightest clue of how even to approach this question, as we saw. In my view, the problem is that we are asking an unclear question, because we are unclear about what the “seeing” is supposed in the first place to be. This is the complacency that I mentioned previously.

So I will press on and look for a way of clarifying our everyday concept of seeing – the phenomenon each of us knows from personal experience. Why do we have so much trouble explaining what this phenomenon is, or even what we take it to be?

Part of the difficulty is that, in looking at something, and attempting to focus on the fact that we “see” it, we seem to have nothing to focus on except the thing that we see. In a famous passage, the English philosopher G. E. Moore observed:

This is the notorious diaphanous nature of seeing and it bears a closer look.

We are trying to spell out or otherwise uncover our everyday concept of seeing – the plain man’s concept. It is common knowledge that we see what’s around us, that we see with our eyes, and that we need light to see. But what is our broad conception of the phenomenon? What do we broadly imagine is “taking place” when someone sees?

Consider a man looking at a tree and let us agree that he sees the tree. We have no trouble identifying either the man or the tree, but it is much harder to pin down the “seeing” that is supposed to be occurring here. There is certainly nothing in the picture that we can point to. Nor would adding more detail to the picture help.

Of course, in seeing the tree, the man is not doing anything to the tree. Seeing a tree is not like pruning a tree, so we cannot expect to observe some specific physical action (of the man) directed upon the tree. But what then do we take to be “going on” when we speak of the man seeing the tree? We seem to have no difficulty understanding such talk in practice.

Some people – for whatever reason (see a bit later) – think of seeing as the emergence of a “private bubble of consciousness” on the part of the subject doing the seeing.

The bubble is sometimes located within the subject’s head, but the essential idea is that the contents of the bubble should be “private” to the subject. —The bubble is in his mind, as it were. Of course, the contents of the bubble are supposed – in some sense – to “reflect” the scene around the subject, but the subject’s vision is nevertheless “confined” within the bubble, as the picture unabashedly suggests.

I do not believe that the man on the street supposes any such thing to be going on when he sees. The main reason is that the bubble creates a “barrier” between a subject and the world, whereas, to the plain man, seeing is more like touching, in the sense of being a “direct communion” with the objects around him. In the language of philosophers, seeing is normally supposed to be a diaphanous phenomenon.

This does not mean that the conception above is incorrect. The point is only that it is not attributable to the ordinary man. That is not how the ordinary man thinks of seeing, whether or not it is a correct way of thinking about seeing. (I don’t imagine it can be correct though.)

A related idea is that seeing is the displaying of an image on a screen in the subject’s mind, as though someone was watching television.

This idea is no better than the previous one. No ordinary person thinks of seeing as the displaying of an image on a screen (of any sort). As mentioned, ordinary people accept that they are in “direct visual contact” with what they see.

Besides, even if there was an image on a screen, we would still have to account for the “seeing” of the image, which was precisely the sort of problem we were struggling with. So the introduction of the screen serves no real purpose.

What then is the plain man’s conception of seeing, if not anything like the above? Articulating it seems so hard that one feels simply like drawing an arrow and proclaiming that seeing is just the “directedness” of the man’s attention upon the tree.

Needless to say, this verges on desperation. Nothing like an arrow actually emerges from the man’s eyes nor does anyone suppose as much. And while the man’s attention is doubtless directed upon the tree, pointing this out is no clearer than saying simply that he sees the tree. So this account is not much better than waving one’s hands before one’s eyes in order to explain the concept of seeing.

Our question is what the plain man takes to be “going on” when he sees something. In attempting to answer this question, remember that there is no point giving the scientific account of what is going on – the one involving photons striking the retina and signals being sent to the visual cortex.

An ancient Egyptian would certainly have had the concept of seeing and could very well have asked himself what his concept of it was. This would be the same question that we are asking ourselves right now, and we would expect it to be answered in the same way. The answer clearly will not refer to anything like photons or the brain.

I mentioned above that our current difficulty is just an instance of the more general difficulty of explaining what consciousness is supposed to be. (Visual consciousness – or seeing – is just a special case.) We accept that we are “conscious” creatures – e.g., I am conscious right now of numerous things transpiring around me – but it is no less hard to explain what we take this phenomenon of “consciousness” to be.

Many philosophers readily admit a difficulty here. David Chalmers says:

Philosophers indeed console themselves by saying that we have a “clear enough” sense of the phenomenon of consciousness, even if we can’t quite capture it in words. As Chalmers suggests, we seem to know what consciousness is from personal experience. And we may be tempted to say the same of seeing – we know what seeing is from personal experience, even if we can’t quite put it in words.Consciousness can be startlingly intense. It is the most vivid of phenomena; nothing is more real to us. But it can be frustratingly diaphanous: in talking about conscious experience, it is notoriously difficult to pin down the subject matter ... What is central to consciousness, at least in the most interesting sense, is experience. But this is not definition. At best, it is clarification.Trying to define conscious experience in terms of more primitive notions is fruitless ... The best we can do is to give illustrations and characterizations that lie at the same level. These characterizations cannot qualify as true definitions, due to their implicitly circular nature, but they can help to pin down what is being talked about. I presume that every reader has conscious experiences of his or her own. If all goes well, these characterizations will help establish that it is just those that we are talking about. (The Conscious Mind, pp. 3–4.)

Consider our man again, who sees the tree.

If pressed to explain what is “going on” with the man when he sees the tree, we might eventually venture that the same sort of thing “goes on” with him as does with us when we see the tree, and we roughly know what this is from personal experience.

Let’s explore this a bit and see if anything comes out of it. Where seeing is concerned, what is it that we know from personal experience?

When we consider our personal experience of seeing in order to get a handle on the concept, we can easily find ourselves moving around in circles:

To see a tree is for the tree to “appear” to me. The tree becomes manifest. It “shows itself.” It becomes there for me!These explications are not particularly helpful. They seem simply to be different ways of emphasizing that I see the tree. In Chalmers’s terms, they are characterizations that “lie at the same level.” So they throw no light on what it is that we know from personal experience.

In frustration, we feel like raising our hands aloft and declaring, “This is seeing!”

Some people are indeed satisfied with this! Conceding that they can’t explain what it is that they know from their “personal experience” of seeing, they feel that they nevertheless know what they are talking about when they talk about seeing.

My own feeling is that this is not good enough. If you take this “practical grasp” of seeing – as we might call it – and go on to ask how this thing – the “seeing” that we know from personal experience – arises from activity in the brain, you run quickly into a dead end. No one has the slightest clue of how even to approach this question, as we saw. In my view, the problem is that we are asking an unclear question, because we are unclear about what the “seeing” is supposed in the first place to be. This is the complacency that I mentioned previously.

So I will press on and look for a way of clarifying our everyday concept of seeing – the phenomenon each of us knows from personal experience. Why do we have so much trouble explaining what this phenomenon is, or even what we take it to be?

Part of the difficulty is that, in looking at something, and attempting to focus on the fact that we “see” it, we seem to have nothing to focus on except the thing that we see. In a famous passage, the English philosopher G. E. Moore observed:

Likewise, if I look at a tree, and try to focus on the fact that I see the tree, it is difficult to pin down the “seeing” because I seem to have nothing to focus on except the tree. The “seeing” seems to vanish into emptiness, as Moore puts it.The moment we try to fix our attention upon consciousness and to see what, distinctly, it is, it seems to vanish: it seems as if we had before us a mere emptiness. When we try to introspect the sensation of blue, all we can see is the blue: the other element is as if it were diaphanous. (‘The Refutation of Idealism,’ p. 450.)

This is the notorious diaphanous nature of seeing and it bears a closer look.

Menu

What’s a logical paradox?

What’s a logical paradox? Achilles & the tortoise

Achilles & the tortoise The surprise exam

The surprise exam Newcomb’s problem

Newcomb’s problem Newcomb’s problem (sassy version)

Newcomb’s problem (sassy version) Seeing and being

Seeing and being Logic test!

Logic test! Philosophers say the strangest things

Philosophers say the strangest things Favourite puzzles

Favourite puzzles Books on consciousness

Books on consciousness Philosophy videos

Philosophy videos Phinteresting

Phinteresting Philosopher biographies

Philosopher biographies Philosopher birthdays

Philosopher birthdays Draft

Draftbarang 2009-2024  wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine