Seeing and being

Preface

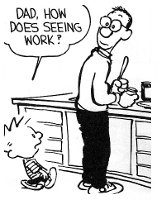

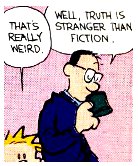

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

15. Loose ends

This has really been an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness, often described as the problem of explaining how seeing (or visual experience) – to take our special case – “arises” from activity in the brain.

I suggested at the start that this way of raising the problem was premature because of our poor grasp of the concept of “seeing.” But, having now alleged to have clarified the concept, what becomes of the hard problem?

The proposed clarification was this:

This doesn’t make the “hard problem” go away, however, but merely forces it to assume a different form. For what certainly does occur inside your head when you see a chair is a certain pattern of activity in your visual cortex – let’s say. Indeed, we know enough about the brain to know that if your visual cortex were appropriately stimulated “from the inside,” then it would seem to you as if you were seeing a chair. (This is what happens when we dream.) This is what prompts people to say that seeing “arises” from activity in the brain. Moreover, in a normal case of seeing, our visual cortex is stimulated “from the outside” by whatever we then find ourselves seeing. So essentially the same thing appears to happen here – our visual cortex is stimulated, and then we see. Now, if activity in the brain does not cause the phenomenon of seeing to occur, how should we understand this “strange link” between cortical activity and seeing?

Let’s make this a little more vivid. On the view being proposed, cortical activity in my brain is apparently able to “bring into being” something out there for me to discover – e.g., a certain part of a chair, or a room, or whatever. This is what the “strange link” comes down to, on the view that seeing something is just its partial being. If we decline to call this a case of causation, then we need an alternative account of what then is going on, because we are being saddled with something pretty strange here. Consider the case of a dream, where the idea is perhaps a little more familiar. We are all used to the idea that activity in our sleeping brain can somehow “bring into being” a “virtual world” for us to “inhabit,” even if we have difficulty grasping how a “virtual world” can thus be conjured up at all. But, in a normal case of seeing, the corresponding idea would have to be that activity in our waking brain somehow “brings into being” various parts of the real world that we find ourselves inhabiting – a world, moreover, that contains the very brain activity at issue. What sense can we possibly make of this?

To some, this may seem like a reductio of the entire position – it has led to a nonsensical outcome. But I think rather that this is simply the “hard problem” in a new guise. I would add that it is a problem that we are better prepared to tackle because we can be more confident that we are asking the right kind of question. It is obviously a completely different kind of question from the one raised by the traditional “hard problem” of consciousness, and so it really does matter to ask the right question. And while I’m not entirely sure of the best way to resolve our new “hard problem,” it is not difficult to find meaningful suggestions. Let me sketch one approach that may point in the right direction.

I have suggested that the concept of seeing is just the concept of “precipitated” partial being, but have said little about what sort of phenomenon a “precipitation” is supposed to be. This is starting to get crucial so we need to get a better handle on it.

A precipitation of a partial world is something that we are entirely familiar with since we “inhabit” such partial worlds all the time. As I type, what precipitates for me is the screen on which these words are appearing, along with numerous other background events like the movement of my fingers on the keyboard, the traffic outside my window, and so on. (Each of us can no doubt say something similar.) In other words, a precipitation is a little cross-section of reality “come into being,” as it were. That is not how we normally think of it, of course, since, as before, it makes no ordinary sense for us to suppose that all that exists is a cross-section of reality. Rather, we normally think of a precipitation as a case of seen being – or perceived being, or known being, more generally – employing a conceptual apparatus whose origin I have endeavoured in this essay to explain. For all that, at some level of description or other – one level down as it were – all that “goes on,” very roughly speaking, is that these little cross-sections of reality flit in and out of existence for each of us. What is this phenomenon? Where do these cross-sections of reality come from? How do they arise and what explains how we come to find ourselves “in them”?

It would take another essay to spell out even a semblance of an account here, but our immediate problem is only to make sense of certain “strange links” between activity in our brains and the stuff of our precipitations. How can what happens in my brain have any “influence” on what precipitates for me – i.e., on what I discover to be happening in a certain part of reality, e.g., in my room? How can cortical activity in my brain “influence” what I find on my table?

In trying to make sense of this phenomenon, it helps to consider a simpler case of it, involving something less esoteric than activity in the brain. Consider how the world “appears” when we open our eyes and “vanishes” when we shut them. We are so used to this phenomenon that we no longer find it strange, but this is essentially the same kind of “influence” as that enjoyed by brain activity – only simpler. Opening my eyes can seemingly “dictate” that something exists “out there” to be found – how should we understand what is going on here? This case is simpler because, while brain activity can “dictate” what I find out there, eye activity at most “dictates” that I find something out there, and not what it is. In either case, however, events happening with my body seem able to “bring into being” a part of the external world. Nothing like this is a part of our ordinary understanding of the world that we inhabit, so how do we “make place” for it? – this is the essential problem.

In the case of eye activity, the “standard account,” of course, is that opening my eyes allows light into my head, which sets off a sequence of brain events that culminates in the occurrence of a “visual experience” in the vicinity of my head. On this account, opening my eyes does not literally “bring the world into being,” which may sound like a load of nonsense, but simply causes it to be seen – a different thing altogether. This sounds nice and sensible, but only until we realize that putting it this way simply hides the “nonsense” in a different place. For we must now confront the traditional “hard problem” of explaining how the visual experience – whatever this is – “arises” at the end of the cranial causal chain, which is just another form of nonsense, really – the standard nonsense. The truth is that it has always seemed nonsensical how opening our eyes “enables” us to see. The apparent nonsense that infects our account is simply different from that which infects the standard account, and the question is only how to “make sense” of the apparent nonsense.

The case of eye activity is useful for our purposes because it helps us sketch an answer which can then be extended to the slightly more complex case of brain activity. And so here is the sketch promised above.

I think the correct approach, in our case, is to hold that what precipitates for us is not given to us “fully interpreted,” as if we were merely passive observers. Rather, we are compelled to “interpret” our precipitations in ways that enable us to discern patterns or regularities within them which serve to give them “predictive coherence,” as it were – which enables us to make sense of what is “going on” at all. This includes regularties governing impersonal things, e.g., that closer things occlude ones that are further away, or that spherical things look the same from any angle, but – crucially – also regularties relating what we do and what precipitates in response, e.g., that turning around eventually brings things back to where they were. If we failed to find such regularities within our precipitations, I believe that we would not be able to “make sense” of them at all. For example, a baby takes a while to master its visual world because it has to figure out not just what it is seeing but also what it is doing, and how the one correlates with the other. If a baby failed to grasp that it had a head, over which it had some control, and that what it saw was always in front of its head, no matter how it moved its head, then it would have a hard time figuring out what was going on – it would be unable to make sense of what it was “seeing,” or even that any “seeing” was occurring at all.

Indeed, the state of our bodies is a relatively important part of what precipitates for us, whenever anything precipitates at all. This is easy to overlook, but if you find yourself looking at a painting (say), then you know all sorts of things, not just about the painting, but also about the relation of your body to the painting, including the fact that you are facing the painting and that your eyes are open. The point is that it is not given to you that your eyes are open or that you are facing the painting, or even that you have eyes or a body at all – this is a part of your “intepretation” of what is going on. Likewise, such a regularity as that the world “disappears” when we shut our eyes and “reappears” when we open them again is not so much a strange influence of a bodily event upon external reality, as a regularity that we have been persuaded to “interpret into existence,” or perhaps to “negotiate into existence,” as part of our effort to make sense of what is going on at all. Some such regularities must exist in our precipitations because, if we did not “find them” there, nothing would precipitate for us at all.

This is essentially an anthropic explanation of the “strange link” that exists between our eye movements and our ability to see. It is clearly a very different kind of explanation from that offered by the “standard account” alluded to above, but not essentially different from that suggested by some philosophers of science for why our universe contains regularities at all. (“If it did not, we wouldn’t be here to ask the question.”) The corresponding links between brain activity and the contents of our precipitations can be explained in a very similar way, just one level deeper. Activity in the visual cortex does not “bring into being” a partial chair for me to discover any more than opening my eyes “brings into being” a partial world for me to discover. At least, not literally – that would be the “nonsensical” way of putting it. The correlation between cortical activity and the partial chair before me owes rather to the fact that this is one of those regularities – a considerably more advanced one – that I have “negotiated” or “bargained” into existence, on pain of nothing precipitating for me at all, or else ending up with “relatively impoverished” precipitations. The astronomer Carl Sagan expresses this anthropic point in this way:

This is the barest sketch of a possible answer to our “hard problem,” but it is all that I can manage here. The main thing I am endeavouring to show is that the road ahead is not blocked and that we have room to manoeuvre. To take things further, we would need a fuller account of the notion of a “precipitation,” but I don’t have one at hand yet. Nevertheless, I am merely trying to wind down a pretty long essay, and so I think this speculative effort is okay. This is supposed to be a section on loose ends, and I have just scratched the surface of one of the looser ones. We had better move on, however, because other pressing questions about precipitations deserve to be mentioned, as well as a couple of other important things.

Here are some other quick questions about precipitations that bother me a bit. Do precipitations occur in time? Or is time rather a “construct” that is “internal” to our precipitations, in the way that one might quite naturally suppose space to be? My instinct says that it is, but I do not really know how to get started on “spelling out” the concept of time – this is Augustine’s problem from our point of view, and it seems to me quite a hard one. But forget about time – how does a self get into a precipitation? I find myself embedded within a precipitation – and I don’t just mean my body. Am I myself a “construct” too? And what about other selves? What are these? Do they inhabit precipitations to which I myself have no access? And so on – a full-fledged account of the “metaphysics” of a precipitation is clearly needed here. A third question, of a different sort, concerns whether precipitations consist of neutral “raw material” which we subsequently “interpret.” If so, what is this neutral raw material? If not, how do the “interpretations” get off the ground at all? I haven’t figured out reasonable answers to any of these questions, so I think I should just concede this here and leave the speculative metaphysics behind.

A completely different issue is the generalization of the given account from seeing to knowing. Let’s consider this a little as it is quite important too. I have treated seeing as a paradigm case of knowing and have suggested at various points that the proposed account of seeing would generalize without difficulty to the case of knowing. Am I suggesting then that the phenomenon of knowing too is nothing more than the phenomenon of precipitated partial being? The answer is yes – at least where empirical knowledge is concerned. (I set aside things like mathematical knowledge.) But how would this work? Suppose I know that a man is standing outside my door – e.g., because a neighbour tells me so. There is no apparent precipitation of the man here, unlike if I see the man for myself. So how can “mere knowing” be a case of precipitated partial being?

This issue is quite large and I cannot cover everything but, where the man at the door is concerned, the essential answer is that the notion of “partiality” is really a little more flexible than I have so far made it out to be. I said earlier that a partial being is a spatio-temporal cross-section of reality and talked briefly about conical and spherical cross-sections, as though geometry was the primary consideration. This was actually quite rigid, since reality can be “partial” in many different ways. When you see things at night, for example, reality is “attenuated” for you, but not essentially in a spatio-temporal way – you may see that a “dark” van is outside your gate without being able to make out its exact colour. This “darkness” is a form of precipitated being, though one indeterminate in point of colour. So partiality of being may take the form of “indeterminacy,” rather than spatio-temporal constriction, although, in the case of the van, both are involved. And if you know simply that a van is outside your gate – e.g., because someone told you so – then the indeterminacy in question is even greater, but we can still meaningfully speak here of a van having precipitated for you, just one of indeterminate dimensions and colour.

The ‘partial’ in ‘partial being,’ in other words, is not essentially a geometrical notion. And so a “part” or “slice” or “cross-section” of reality should not be thought of primarily in the way that a phenomenalist or an idealist might be inclined to do, as though it referred to something that might be captured in a well-taken colour photograph. (I engaged in this pretence previously, but only for simplicity.) Indeed, it seems to me that there is no sharp line between seeing that a man is at the door and “merely knowing” that he is at the door. There are any number of in-between cases, e.g., seeing the man in dim light, or in silhouette, or shrouded by a blanket, or seeing his shadow, or hearing his footsteps instead of seeing him, or inferring his presence from a whiff of his cologne, or the growl of your dog, etc. In each of these cases, some “slice” of the world – drawn from a rich and diverse family of slices – is “real” for you, and we can meaningfully speak of a partial world as having precipitated, viz., whatever slice of the world you happen to be apprised of, in whatever limited way.

Aside from these specific considerations, however, I am inclined to accept that knowing is precipitated partial being simply because our previous considerations involving the “omnivisual being” generalize without difficulty to the case of knowing. Echoing our earlier train of thought, consider that an omniscient being – one who knows everything – would have no essential need for the distinction between something’s being true and his knowing it to be true. The distinction would “collapse” for him in the way that the distinction between seeing and being would collapse for an omnivisual being. And so we are led to the corresponding thesis that knowing is precipitated partial being, i.e., following the route we took in the case of seeing. This general consideration is perhaps even more important than the specific ones above. Overall, then, seeing is a case of knowing, and knowing is precipitated partial being, where being (in turn) is just potential knowing. This is the complete generalization that I would be prepared to defend.

I have sometimes spoken of seeing and being, or knowing and being, as if they were spokesmen for the general notions of “mind” and “world.” It seems clear, however, that even if we understood both seeing and knowing, we would be far from understanding the concept of mind in general. There are other important mental notions like thinking, wanting and feeling that I have said nothing about. I have also said little about “sensory qualities” like heat and pain, or the “secondary qualities” in general, including sound, smell and taste. I would imagine that the proposed account of seeing would extend readily to (at least) hearing, tasting and smelling, but one may have doubts even about this. Is there such a thing as the diaphanousness of smelling, for example? Many people think that, strictly speaking, we only ever smell the smell exuded by things, and not the things themselves, and similar sentiments are often expressed about hearing and taste. This raises complications that we have not encountered at all – e.g., what is a smell? This sort of question does not arise for seeing because it is not reasonable to hold that we only ever see the look of things, and not the things themselves. So it is possible that the case of seeing is (deceptively) simpler and that no straightforward generalization to the other senses is possible.

All of this relates to an issue that has so far been in the background. A central feature of the proposed account was that the notions of seeing and being are “cleaved apart” from one another in our conceptual scheme, i.e., rather than acquired separately, as we normally tend to suppose. If the same could be shown of the general notions of “mind” and “world,” it would constitute a significant conceptual discovery. Given what was said in the previous paragraph, however, we are not really anywhere near this, although that is the broad direction in which I am tempted to head. That would be a fully general “neutral monism.”

Even sticking to seeing, however, many important things have not been addressed. The phenomenon of colour, for example, deserves considerably more attention than I have given it. I suggested that the layman would consider colour to be something “out there” in the world, rather than a pure concoction of the mind, as some scientists and philosophers tend to think. But the difficulties – both scientific and philosophical – involved in placing colour “out there” in the world are close to legendary. I won’t try to recount these here, but simply concede that anyone – like me – who is impressed by the diaphanousness of seeing, and who is thus tempted to locate colour “out there” in the world, owes us an account of what colour could possibly be, consistent with our current understanding of the nature of physical reality. The problem is that we have no apparent need to recognize any such property as that of colour – as the layman thinks of it – in our extant conceptions of physical reality.

The final issue I should mention is that of accounting for perceptual illusions and hallucinations – episodes of “false vision” in the case of seeing. Some philosophers consider this matter to be so central that they have practically designed their theories “around” it. I have always thought it best to tackle this last of all, however, once a reasonable account of paradigm cases of seeing has been secured. Having now proposed one such account, I think I can indeed be brief. The account of “false vision” that fits most naturally with the proposed account is simply that suggested by the idealist or the phenomenalist, viz., that they are simply “wayward bits” of precipitated reality that contradict or fail in some way to “cohere” with the other bits that otherwise tell a coherent story. They are cases, as it were, of unbeen seeing. There are obviously details to be filled in here, not least of which why there should be such things as illusions and hallucinations at all, and whether this account of “false vision” can be generalized to cover “false knowledge” as well, but the net result will be something like a “coherence” theory of truth, rather than a “correspondence” theory. For some happy reason, though, I have always been partial to this.

This has really been an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness, often described as the problem of explaining how seeing (or visual experience) – to take our special case – “arises” from activity in the brain.

I suggested at the start that this way of raising the problem was premature because of our poor grasp of the concept of “seeing.” But, having now alleged to have clarified the concept, what becomes of the hard problem?

The proposed clarification was this:

Seeing is (precipitated) partial being;

Being is potential seeing.

From this point of view, there is no evident sense in which seeing can be said to “arise” from the brain. The seeing of a chair, for instance, is just the “partial being” of a certain cross-section of the chair. It is not an “additional event” (over and above the partial being of the chair) that occurs inside your head, or anywhere else. And so it doesn’t “arise” from the brain any more than the relevant part of the chair does. In other words, there is no evident sense in which brain activity causes the phenomenon of seeing.Being is potential seeing.

This doesn’t make the “hard problem” go away, however, but merely forces it to assume a different form. For what certainly does occur inside your head when you see a chair is a certain pattern of activity in your visual cortex – let’s say. Indeed, we know enough about the brain to know that if your visual cortex were appropriately stimulated “from the inside,” then it would seem to you as if you were seeing a chair. (This is what happens when we dream.) This is what prompts people to say that seeing “arises” from activity in the brain. Moreover, in a normal case of seeing, our visual cortex is stimulated “from the outside” by whatever we then find ourselves seeing. So essentially the same thing appears to happen here – our visual cortex is stimulated, and then we see. Now, if activity in the brain does not cause the phenomenon of seeing to occur, how should we understand this “strange link” between cortical activity and seeing?

Let’s make this a little more vivid. On the view being proposed, cortical activity in my brain is apparently able to “bring into being” something out there for me to discover – e.g., a certain part of a chair, or a room, or whatever. This is what the “strange link” comes down to, on the view that seeing something is just its partial being. If we decline to call this a case of causation, then we need an alternative account of what then is going on, because we are being saddled with something pretty strange here. Consider the case of a dream, where the idea is perhaps a little more familiar. We are all used to the idea that activity in our sleeping brain can somehow “bring into being” a “virtual world” for us to “inhabit,” even if we have difficulty grasping how a “virtual world” can thus be conjured up at all. But, in a normal case of seeing, the corresponding idea would have to be that activity in our waking brain somehow “brings into being” various parts of the real world that we find ourselves inhabiting – a world, moreover, that contains the very brain activity at issue. What sense can we possibly make of this?

To some, this may seem like a reductio of the entire position – it has led to a nonsensical outcome. But I think rather that this is simply the “hard problem” in a new guise. I would add that it is a problem that we are better prepared to tackle because we can be more confident that we are asking the right kind of question. It is obviously a completely different kind of question from the one raised by the traditional “hard problem” of consciousness, and so it really does matter to ask the right question. And while I’m not entirely sure of the best way to resolve our new “hard problem,” it is not difficult to find meaningful suggestions. Let me sketch one approach that may point in the right direction.

I have suggested that the concept of seeing is just the concept of “precipitated” partial being, but have said little about what sort of phenomenon a “precipitation” is supposed to be. This is starting to get crucial so we need to get a better handle on it.

A precipitation of a partial world is something that we are entirely familiar with since we “inhabit” such partial worlds all the time. As I type, what precipitates for me is the screen on which these words are appearing, along with numerous other background events like the movement of my fingers on the keyboard, the traffic outside my window, and so on. (Each of us can no doubt say something similar.) In other words, a precipitation is a little cross-section of reality “come into being,” as it were. That is not how we normally think of it, of course, since, as before, it makes no ordinary sense for us to suppose that all that exists is a cross-section of reality. Rather, we normally think of a precipitation as a case of seen being – or perceived being, or known being, more generally – employing a conceptual apparatus whose origin I have endeavoured in this essay to explain. For all that, at some level of description or other – one level down as it were – all that “goes on,” very roughly speaking, is that these little cross-sections of reality flit in and out of existence for each of us. What is this phenomenon? Where do these cross-sections of reality come from? How do they arise and what explains how we come to find ourselves “in them”?

It would take another essay to spell out even a semblance of an account here, but our immediate problem is only to make sense of certain “strange links” between activity in our brains and the stuff of our precipitations. How can what happens in my brain have any “influence” on what precipitates for me – i.e., on what I discover to be happening in a certain part of reality, e.g., in my room? How can cortical activity in my brain “influence” what I find on my table?

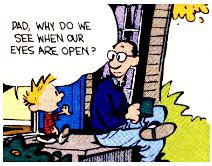

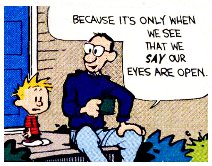

In trying to make sense of this phenomenon, it helps to consider a simpler case of it, involving something less esoteric than activity in the brain. Consider how the world “appears” when we open our eyes and “vanishes” when we shut them. We are so used to this phenomenon that we no longer find it strange, but this is essentially the same kind of “influence” as that enjoyed by brain activity – only simpler. Opening my eyes can seemingly “dictate” that something exists “out there” to be found – how should we understand what is going on here? This case is simpler because, while brain activity can “dictate” what I find out there, eye activity at most “dictates” that I find something out there, and not what it is. In either case, however, events happening with my body seem able to “bring into being” a part of the external world. Nothing like this is a part of our ordinary understanding of the world that we inhabit, so how do we “make place” for it? – this is the essential problem.

In the case of eye activity, the “standard account,” of course, is that opening my eyes allows light into my head, which sets off a sequence of brain events that culminates in the occurrence of a “visual experience” in the vicinity of my head. On this account, opening my eyes does not literally “bring the world into being,” which may sound like a load of nonsense, but simply causes it to be seen – a different thing altogether. This sounds nice and sensible, but only until we realize that putting it this way simply hides the “nonsense” in a different place. For we must now confront the traditional “hard problem” of explaining how the visual experience – whatever this is – “arises” at the end of the cranial causal chain, which is just another form of nonsense, really – the standard nonsense. The truth is that it has always seemed nonsensical how opening our eyes “enables” us to see. The apparent nonsense that infects our account is simply different from that which infects the standard account, and the question is only how to “make sense” of the apparent nonsense.

The case of eye activity is useful for our purposes because it helps us sketch an answer which can then be extended to the slightly more complex case of brain activity. And so here is the sketch promised above.

I think the correct approach, in our case, is to hold that what precipitates for us is not given to us “fully interpreted,” as if we were merely passive observers. Rather, we are compelled to “interpret” our precipitations in ways that enable us to discern patterns or regularities within them which serve to give them “predictive coherence,” as it were – which enables us to make sense of what is “going on” at all. This includes regularties governing impersonal things, e.g., that closer things occlude ones that are further away, or that spherical things look the same from any angle, but – crucially – also regularties relating what we do and what precipitates in response, e.g., that turning around eventually brings things back to where they were. If we failed to find such regularities within our precipitations, I believe that we would not be able to “make sense” of them at all. For example, a baby takes a while to master its visual world because it has to figure out not just what it is seeing but also what it is doing, and how the one correlates with the other. If a baby failed to grasp that it had a head, over which it had some control, and that what it saw was always in front of its head, no matter how it moved its head, then it would have a hard time figuring out what was going on – it would be unable to make sense of what it was “seeing,” or even that any “seeing” was occurring at all.

Indeed, the state of our bodies is a relatively important part of what precipitates for us, whenever anything precipitates at all. This is easy to overlook, but if you find yourself looking at a painting (say), then you know all sorts of things, not just about the painting, but also about the relation of your body to the painting, including the fact that you are facing the painting and that your eyes are open. The point is that it is not given to you that your eyes are open or that you are facing the painting, or even that you have eyes or a body at all – this is a part of your “intepretation” of what is going on. Likewise, such a regularity as that the world “disappears” when we shut our eyes and “reappears” when we open them again is not so much a strange influence of a bodily event upon external reality, as a regularity that we have been persuaded to “interpret into existence,” or perhaps to “negotiate into existence,” as part of our effort to make sense of what is going on at all. Some such regularities must exist in our precipitations because, if we did not “find them” there, nothing would precipitate for us at all.

This is essentially an anthropic explanation of the “strange link” that exists between our eye movements and our ability to see. It is clearly a very different kind of explanation from that offered by the “standard account” alluded to above, but not essentially different from that suggested by some philosophers of science for why our universe contains regularities at all. (“If it did not, we wouldn’t be here to ask the question.”) The corresponding links between brain activity and the contents of our precipitations can be explained in a very similar way, just one level deeper. Activity in the visual cortex does not “bring into being” a partial chair for me to discover any more than opening my eyes “brings into being” a partial world for me to discover. At least, not literally – that would be the “nonsensical” way of putting it. The correlation between cortical activity and the partial chair before me owes rather to the fact that this is one of those regularities – a considerably more advanced one – that I have “negotiated” or “bargained” into existence, on pain of nothing precipitating for me at all, or else ending up with “relatively impoverished” precipitations. The astronomer Carl Sagan expresses this anthropic point in this way:

Sagan expresses the point in the normal way, but it is easily adapted to our current language of precipitations. The “patterns and rules” that we find among our precipitations may, in some sense, be considered brute, but they are brute in a Kantian (“transcendental”) sense which allows us to understand why anything like them should exist at all.If we lived on a planet where nothing ever changed, there wouldn’t be much to do; there’d be nothing to figure out; there’d be no impetus for science. And if we lived in an unpredictable world, where things changed in random or very complex ways, we wouldn’t be able to figure things out, and, again, there’d be no such thing as science. But we live in an in-between universe, where things change all right, but according to patterns, rules, or, as we call them, laws of nature ... and so it’s possible to figure things out. We can do science, and, with it, we can improve our lives. (Cosmos, Episode 3.)

This is the barest sketch of a possible answer to our “hard problem,” but it is all that I can manage here. The main thing I am endeavouring to show is that the road ahead is not blocked and that we have room to manoeuvre. To take things further, we would need a fuller account of the notion of a “precipitation,” but I don’t have one at hand yet. Nevertheless, I am merely trying to wind down a pretty long essay, and so I think this speculative effort is okay. This is supposed to be a section on loose ends, and I have just scratched the surface of one of the looser ones. We had better move on, however, because other pressing questions about precipitations deserve to be mentioned, as well as a couple of other important things.

Here are some other quick questions about precipitations that bother me a bit. Do precipitations occur in time? Or is time rather a “construct” that is “internal” to our precipitations, in the way that one might quite naturally suppose space to be? My instinct says that it is, but I do not really know how to get started on “spelling out” the concept of time – this is Augustine’s problem from our point of view, and it seems to me quite a hard one. But forget about time – how does a self get into a precipitation? I find myself embedded within a precipitation – and I don’t just mean my body. Am I myself a “construct” too? And what about other selves? What are these? Do they inhabit precipitations to which I myself have no access? And so on – a full-fledged account of the “metaphysics” of a precipitation is clearly needed here. A third question, of a different sort, concerns whether precipitations consist of neutral “raw material” which we subsequently “interpret.” If so, what is this neutral raw material? If not, how do the “interpretations” get off the ground at all? I haven’t figured out reasonable answers to any of these questions, so I think I should just concede this here and leave the speculative metaphysics behind.

A completely different issue is the generalization of the given account from seeing to knowing. Let’s consider this a little as it is quite important too. I have treated seeing as a paradigm case of knowing and have suggested at various points that the proposed account of seeing would generalize without difficulty to the case of knowing. Am I suggesting then that the phenomenon of knowing too is nothing more than the phenomenon of precipitated partial being? The answer is yes – at least where empirical knowledge is concerned. (I set aside things like mathematical knowledge.) But how would this work? Suppose I know that a man is standing outside my door – e.g., because a neighbour tells me so. There is no apparent precipitation of the man here, unlike if I see the man for myself. So how can “mere knowing” be a case of precipitated partial being?

This issue is quite large and I cannot cover everything but, where the man at the door is concerned, the essential answer is that the notion of “partiality” is really a little more flexible than I have so far made it out to be. I said earlier that a partial being is a spatio-temporal cross-section of reality and talked briefly about conical and spherical cross-sections, as though geometry was the primary consideration. This was actually quite rigid, since reality can be “partial” in many different ways. When you see things at night, for example, reality is “attenuated” for you, but not essentially in a spatio-temporal way – you may see that a “dark” van is outside your gate without being able to make out its exact colour. This “darkness” is a form of precipitated being, though one indeterminate in point of colour. So partiality of being may take the form of “indeterminacy,” rather than spatio-temporal constriction, although, in the case of the van, both are involved. And if you know simply that a van is outside your gate – e.g., because someone told you so – then the indeterminacy in question is even greater, but we can still meaningfully speak here of a van having precipitated for you, just one of indeterminate dimensions and colour.

The ‘partial’ in ‘partial being,’ in other words, is not essentially a geometrical notion. And so a “part” or “slice” or “cross-section” of reality should not be thought of primarily in the way that a phenomenalist or an idealist might be inclined to do, as though it referred to something that might be captured in a well-taken colour photograph. (I engaged in this pretence previously, but only for simplicity.) Indeed, it seems to me that there is no sharp line between seeing that a man is at the door and “merely knowing” that he is at the door. There are any number of in-between cases, e.g., seeing the man in dim light, or in silhouette, or shrouded by a blanket, or seeing his shadow, or hearing his footsteps instead of seeing him, or inferring his presence from a whiff of his cologne, or the growl of your dog, etc. In each of these cases, some “slice” of the world – drawn from a rich and diverse family of slices – is “real” for you, and we can meaningfully speak of a partial world as having precipitated, viz., whatever slice of the world you happen to be apprised of, in whatever limited way.

Aside from these specific considerations, however, I am inclined to accept that knowing is precipitated partial being simply because our previous considerations involving the “omnivisual being” generalize without difficulty to the case of knowing. Echoing our earlier train of thought, consider that an omniscient being – one who knows everything – would have no essential need for the distinction between something’s being true and his knowing it to be true. The distinction would “collapse” for him in the way that the distinction between seeing and being would collapse for an omnivisual being. And so we are led to the corresponding thesis that knowing is precipitated partial being, i.e., following the route we took in the case of seeing. This general consideration is perhaps even more important than the specific ones above. Overall, then, seeing is a case of knowing, and knowing is precipitated partial being, where being (in turn) is just potential knowing. This is the complete generalization that I would be prepared to defend.

I have sometimes spoken of seeing and being, or knowing and being, as if they were spokesmen for the general notions of “mind” and “world.” It seems clear, however, that even if we understood both seeing and knowing, we would be far from understanding the concept of mind in general. There are other important mental notions like thinking, wanting and feeling that I have said nothing about. I have also said little about “sensory qualities” like heat and pain, or the “secondary qualities” in general, including sound, smell and taste. I would imagine that the proposed account of seeing would extend readily to (at least) hearing, tasting and smelling, but one may have doubts even about this. Is there such a thing as the diaphanousness of smelling, for example? Many people think that, strictly speaking, we only ever smell the smell exuded by things, and not the things themselves, and similar sentiments are often expressed about hearing and taste. This raises complications that we have not encountered at all – e.g., what is a smell? This sort of question does not arise for seeing because it is not reasonable to hold that we only ever see the look of things, and not the things themselves. So it is possible that the case of seeing is (deceptively) simpler and that no straightforward generalization to the other senses is possible.

All of this relates to an issue that has so far been in the background. A central feature of the proposed account was that the notions of seeing and being are “cleaved apart” from one another in our conceptual scheme, i.e., rather than acquired separately, as we normally tend to suppose. If the same could be shown of the general notions of “mind” and “world,” it would constitute a significant conceptual discovery. Given what was said in the previous paragraph, however, we are not really anywhere near this, although that is the broad direction in which I am tempted to head. That would be a fully general “neutral monism.”

Even sticking to seeing, however, many important things have not been addressed. The phenomenon of colour, for example, deserves considerably more attention than I have given it. I suggested that the layman would consider colour to be something “out there” in the world, rather than a pure concoction of the mind, as some scientists and philosophers tend to think. But the difficulties – both scientific and philosophical – involved in placing colour “out there” in the world are close to legendary. I won’t try to recount these here, but simply concede that anyone – like me – who is impressed by the diaphanousness of seeing, and who is thus tempted to locate colour “out there” in the world, owes us an account of what colour could possibly be, consistent with our current understanding of the nature of physical reality. The problem is that we have no apparent need to recognize any such property as that of colour – as the layman thinks of it – in our extant conceptions of physical reality.

The final issue I should mention is that of accounting for perceptual illusions and hallucinations – episodes of “false vision” in the case of seeing. Some philosophers consider this matter to be so central that they have practically designed their theories “around” it. I have always thought it best to tackle this last of all, however, once a reasonable account of paradigm cases of seeing has been secured. Having now proposed one such account, I think I can indeed be brief. The account of “false vision” that fits most naturally with the proposed account is simply that suggested by the idealist or the phenomenalist, viz., that they are simply “wayward bits” of precipitated reality that contradict or fail in some way to “cohere” with the other bits that otherwise tell a coherent story. They are cases, as it were, of unbeen seeing. There are obviously details to be filled in here, not least of which why there should be such things as illusions and hallucinations at all, and whether this account of “false vision” can be generalized to cover “false knowledge” as well, but the net result will be something like a “coherence” theory of truth, rather than a “correspondence” theory. For some happy reason, though, I have always been partial to this.

Menu

What’s a logical paradox?

What’s a logical paradox? Achilles & the tortoise

Achilles & the tortoise The surprise exam

The surprise exam Newcomb’s problem

Newcomb’s problem Newcomb’s problem (sassy version)

Newcomb’s problem (sassy version) Seeing and being

Seeing and being Logic test!

Logic test! Philosophers say the strangest things

Philosophers say the strangest things Favourite puzzles

Favourite puzzles Books on consciousness

Books on consciousness Philosophy videos

Philosophy videos Phinteresting

Phinteresting Philosopher biographies

Philosopher biographies Philosopher birthdays

Philosopher birthdays Draft

Draftbarang 2009-2024  wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine