7. The last point

Consider the blue dot at the doorway.

We know that Achilles will reach that point in exactly one second, using the numbers in our previous example.

But how, after one second, does Achilles suddenly “escape” from Zeno’s endless sequence and emerge at the doorway?

After all, only a split-second before, we find Achilles at point 85, or point 1,167, or point 345,678, depending on how fine the second is split. The finer it is split, the higher up in Zeno’s sequence we find him to be.

And yet, there, after one second, he has somehow escaped from the sequence altogether. The transition seems incomprehensible. How did he get out of the sequence, if the sequence was endless? Achilles seems to have pulled a Houdini.

If the sequence had a last point, there would be no difficulty. After reaching the last point, Achilles would simply move to the doorway. But without a last point, the final moments that culminate in his reaching the doorway may seem incomprehensible.

Something like this may underlie the essential complaint about the endlessness of Zeno’s sequence. The worry is not easy to articulate, but we can try to sharpen it further.

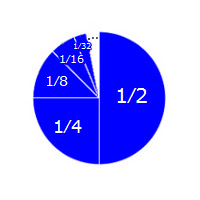

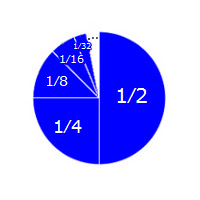

To see the complaint in another way, consider our infinitely-sliced pie again. Imagine adding the slices together, one at a time, to reconstruct the whole pie.

To see the complaint in another way, consider our infinitely-sliced pie again. Imagine adding the slices together, one at a time, to reconstruct the whole pie.

Suppose it takes ½ a second to lay down the first slice, ¼ of a second to lay down the next one, and so on, in exact proportion to size.

Then the entire pie will stand complete after exactly one second.

But this may seem baffling. Slices are being added endlessly, and suddenly, after one second, the pie stands there complete. But there was no final act of completion, only an endless series of acts which kept leaving the pie incomplete. How did the pie suddenly emerge complete after one second?

We can see how the pie can be completed if a last slice is inserted, which final act completes the pie. But, in our case, there is no last slice. So the sudden precipitation of the completed pie seems like a mystery.

We can also see this backwards, as Zeno sometimes urges us to do.

We can also see this backwards, as Zeno sometimes urges us to do.

Suppose we try to construct the pie in the reverse direction, starting with the smallest possible slice, and ending with the largest slice of 1/2.

Of course, there is no such thing as the smallest possible slice, since no matter which slice you pick, there is always a smaller one. It follows that we could never get started!

This is the same complaint, only made in reverse. Since there is no first slice to lay down, we can never get started. In the previous case, there was no last slice to be laid down, and so the pie could never be completed.

In the same way, Zeno sometimes wonders how Achilles can ever get started on any journey. Consider the same situation, but with Achilles beginning at the doorway, and wanting to get to point 1.

Clearly, before he can get there, he must first get to point 2. But before doing so, he must obviously get to point 3. But not before he gets to point 4, and so on, without end.

It seems that Achilles cannot get started! The trouble is that there is no first point to be reached, just as there was no first slice of the pie to be laid down. Without a first point, it seems incomprehensible how Achilles can enter Zeno’s sequence, just as, without a last point, it was incomprehensible how he could exit.

What should we make of these considerations?

Well, before addressing them, it’s worth pausing to examine a famous view which accepts that they are correct! Thus, some people find these considerations completely persuasive and conclude that a last (or first) point in Zeno’s sequence is genuinely demanded, on pain of suffering the absurdities just mentioned.

In other words, they hold that Zeno’s sequence must somehow be “prevented” from going on endlessly in the manner so far contemplated. On their view, the correct lesson to draw is that space is not “infinitely divisible,” as Zeno implicitly assumes it to be.

This solution is easy to appreciate, so let’s consider it first.

Consider the blue dot at the doorway.

We know that Achilles will reach that point in exactly one second, using the numbers in our previous example.

But how, after one second, does Achilles suddenly “escape” from Zeno’s endless sequence and emerge at the doorway?

After all, only a split-second before, we find Achilles at point 85, or point 1,167, or point 345,678, depending on how fine the second is split. The finer it is split, the higher up in Zeno’s sequence we find him to be.

And yet, there, after one second, he has somehow escaped from the sequence altogether. The transition seems incomprehensible. How did he get out of the sequence, if the sequence was endless? Achilles seems to have pulled a Houdini.

If the sequence had a last point, there would be no difficulty. After reaching the last point, Achilles would simply move to the doorway. But without a last point, the final moments that culminate in his reaching the doorway may seem incomprehensible.

Something like this may underlie the essential complaint about the endlessness of Zeno’s sequence. The worry is not easy to articulate, but we can try to sharpen it further.

Suppose it takes ½ a second to lay down the first slice, ¼ of a second to lay down the next one, and so on, in exact proportion to size.

Then the entire pie will stand complete after exactly one second.

But this may seem baffling. Slices are being added endlessly, and suddenly, after one second, the pie stands there complete. But there was no final act of completion, only an endless series of acts which kept leaving the pie incomplete. How did the pie suddenly emerge complete after one second?

We can see how the pie can be completed if a last slice is inserted, which final act completes the pie. But, in our case, there is no last slice. So the sudden precipitation of the completed pie seems like a mystery.

Suppose we try to construct the pie in the reverse direction, starting with the smallest possible slice, and ending with the largest slice of 1/2.

Of course, there is no such thing as the smallest possible slice, since no matter which slice you pick, there is always a smaller one. It follows that we could never get started!

This is the same complaint, only made in reverse. Since there is no first slice to lay down, we can never get started. In the previous case, there was no last slice to be laid down, and so the pie could never be completed.

In the same way, Zeno sometimes wonders how Achilles can ever get started on any journey. Consider the same situation, but with Achilles beginning at the doorway, and wanting to get to point 1.

Clearly, before he can get there, he must first get to point 2. But before doing so, he must obviously get to point 3. But not before he gets to point 4, and so on, without end.

It seems that Achilles cannot get started! The trouble is that there is no first point to be reached, just as there was no first slice of the pie to be laid down. Without a first point, it seems incomprehensible how Achilles can enter Zeno’s sequence, just as, without a last point, it was incomprehensible how he could exit.

What should we make of these considerations?

Well, before addressing them, it’s worth pausing to examine a famous view which accepts that they are correct! Thus, some people find these considerations completely persuasive and conclude that a last (or first) point in Zeno’s sequence is genuinely demanded, on pain of suffering the absurdities just mentioned.

In other words, they hold that Zeno’s sequence must somehow be “prevented” from going on endlessly in the manner so far contemplated. On their view, the correct lesson to draw is that space is not “infinitely divisible,” as Zeno implicitly assumes it to be.

This solution is easy to appreciate, so let’s consider it first.

Menu

What’s a logical paradox?

What’s a logical paradox? Achilles & the tortoise

Achilles & the tortoise The surprise exam

The surprise exam Newcomb’s problem

Newcomb’s problem Newcomb’s problem (sassy version)

Newcomb’s problem (sassy version) Seeing and being

Seeing and being Logic test!

Logic test! Philosophers say the strangest things

Philosophers say the strangest things Favourite puzzles

Favourite puzzles Books on consciousness

Books on consciousness Philosophy videos

Philosophy videos Phinteresting

Phinteresting Philosopher biographies

Philosopher biographies Philosopher birthdays

Philosopher birthdays Draft

Draftbarang 2009-2024  wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

Written in 2009.

Written in 2009. What Is the Answer to Zeno’s Paradox? (2014), by Brian Palmer.

What Is the Answer to Zeno’s Paradox? (2014), by Brian Palmer.