2. Why can’t I try it out for myself and see?

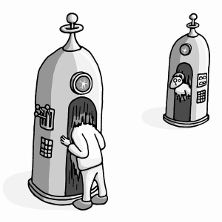

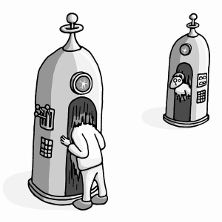

Is the person who emerges from the transporter the same as the one who entered; or just a freshly-minted lookalike, the one who entered having died?

Is the person who emerges from the transporter the same as the one who entered; or just a freshly-minted lookalike, the one who entered having died?

Some people, it must be said, think that there’s no substantial issue here, contending that, in some important sense, the two cited possibilities are one and the same, or that it doesn’t matter which one of them is true, or that they are two different ways of describing the same situation, and so on. A prime example is Parfit himself, who spells out one such view in his book. A view of this sort belongs in a different discussion, however, and I am setting it aside for my purposes. I mean to assume, rather, that the issue raised above is legitimate, and concerns two genuinely distinct possibilities, the only question being which one is true. The line I wish to pursue, thus taking the question at face value, is whether the answer to it can be determined empirically.

Empirically speaking, what everyone agrees on is this: we cannot determine the answer “from the outside,” i.e., from a third-person vantage point. It would be futile to observe someone else enter the machine and thereafter “check” if that same person emerged on Mars: there would be no telling if the person who emerged was the same as the one who entered. The interesting question, however, is whether we can determine the answer “from the inside,” from the first-person point of view. At risk to your own life, could you not try the machine out for yourself in order to see what happens?

This simple first-person check does appear to work in at least one type of case. If there was such a thing as an afterlife, then, if the machine killed you, you’d find yourself waking up in some fiery place like purgatory (say), and you’d realize (let’s presume) that you were dead. Thus:

Kathleen V. Wilkes, Real People: Personal Identity without Thought Experiments. (1988), p. 46, n. 28. Internet Archive.Captain Kirk, so the story goes, disintegrates at place p and reassembles at place p*. But perhaps, instead, he dies at p, and a doppelgänger emerges at p*. What is the difference? One way of illustrating the difference is to suppose there is an afterlife: a heaven, or hell, increasingly supplemented by yet more Captain Kirks all cursing the day they ever stepped into the molecular disintegrator.

This is Kathleen Wilkes, artfully highlighting the uncomfortable possibility conveniently left unmentioned in Star Trek. Her words are to our purpose too: if the transporter killed you, then you could discover this by trying it out, assuming there was such a thing as an afterlife. Of course, if there was no afterlife, then you’d learn nothing: you’d just lose consciousness and it’d be over. But the potential for falsification is clearly there since we cannot in general rule out an afterlife.

If falsification of teleportation is thus possible in principle, what of verification? What happens if the machine worked and really did “send” you to Mars? You’d press the button and find yourself waking up on Mars. Would this assure you in a parallel way that teleportation was real and that you really had been transported to Mars? Take Parfit’s account above:

I press the button. As predicted, I lose and seem at once to regain consciousness, but in a different cubicle. Examining my new body, I find no change at all. Even the cut on my upper lip, from this morning’s shave, is still there.

I press the button. As predicted, I lose and seem at once to regain consciousness, but in a different cubicle. Examining my new body, I find no change at all. Even the cut on my upper lip, from this morning’s shave, is still there.

Would this satisfy Parfit himself, if no one else, that the machine had worked? Would it constitute an empirical verification of teleportation?

As mentioned, the matter is not that simple, because of the following obvious snag. Even if the machine did work, and you did find yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether you were the person who entered the machine, or whether that person died, and you were just a freshly-minted lookalike with false beliefs of having previously entered the machine. After all, anyone—real or copy—who emerged on Mars would “remember” having earlier entered the machine on Earth. So you’d be none the wiser as to whether you were “real” or “copy,” and thus none the wiser as to whether the machine had really worked.

For example, in Dan Dennett’s story, a woman on Mars with a broken spaceship uses a teleporter to get back to Earth. Upon reuniting with her daughter Sarah, it “hits her”:

Am I, really, the same person who kissed this little girl good-bye three years ago? Am I this eight-year-old child’s mother or am I actually a brand-new human being, only several hours old, in spite of my memories—or apparent memories—of days and years before that? Did this child’s mother recently die on Mars, dismantled and destroyed in the chamber of a Teleclone Mark IV? Did I die on Mars? No, certainly I did not die on Mars, since I am alive on Earth. Perhaps, though, someone died on Mars—Sarah’s mother. Then I am not Sarah’s mother. But I must be! The whole point of getting into the Teleclone was to return home to my family! But I keep forgetting; maybe I never got into that Teleclone on Mars. Maybe that was someone else—if it ever happened at all. Is that infernal machine a teleporter—a mode of transportation—or, as the brand name suggests, a sort of murdering twinmaker?

Am I, really, the same person who kissed this little girl good-bye three years ago? Am I this eight-year-old child’s mother or am I actually a brand-new human being, only several hours old, in spite of my memories—or apparent memories—of days and years before that? Did this child’s mother recently die on Mars, dismantled and destroyed in the chamber of a Teleclone Mark IV? Did I die on Mars? No, certainly I did not die on Mars, since I am alive on Earth. Perhaps, though, someone died on Mars—Sarah’s mother. Then I am not Sarah’s mother. But I must be! The whole point of getting into the Teleclone was to return home to my family! But I keep forgetting; maybe I never got into that Teleclone on Mars. Maybe that was someone else—if it ever happened at all. Is that infernal machine a teleporter—a mode of transportation—or, as the brand name suggests, a sort of murdering twinmaker?

So it seems that, if the machine worked, you could not discover this even by trying it out for yourself. This may be why the question is seldom discussed of whether teleportation is subject to empirical test. At least where verification of the phenomenon is concerned—and this is arguably the more important case—the answer may be thought to be obviously no.

This may be thought to settle the matter but, in fact, I will suggest now that the foregoing sceptical thoughts are somewhat confused and essentially incorrect. If the teleporter works, I believe that you can verify this by trying the machine out for yourself. Not always, as I will explain, but at least some of the time, when conditions are favourable in a certain way.

Some people, it must be said, think that there’s no substantial issue here, contending that, in some important sense, the two cited possibilities are one and the same, or that it doesn’t matter which one of them is true, or that they are two different ways of describing the same situation, and so on. A prime example is Parfit himself, who spells out one such view in his book. A view of this sort belongs in a different discussion, however, and I am setting it aside for my purposes. I mean to assume, rather, that the issue raised above is legitimate, and concerns two genuinely distinct possibilities, the only question being which one is true. The line I wish to pursue, thus taking the question at face value, is whether the answer to it can be determined empirically.

Empirically speaking, what everyone agrees on is this: we cannot determine the answer “from the outside,” i.e., from a third-person vantage point. It would be futile to observe someone else enter the machine and thereafter “check” if that same person emerged on Mars: there would be no telling if the person who emerged was the same as the one who entered. The interesting question, however, is whether we can determine the answer “from the inside,” from the first-person point of view. At risk to your own life, could you not try the machine out for yourself in order to see what happens?

This simple first-person check does appear to work in at least one type of case. If there was such a thing as an afterlife, then, if the machine killed you, you’d find yourself waking up in some fiery place like purgatory (say), and you’d realize (let’s presume) that you were dead. Thus:

Kathleen V. Wilkes, Real People: Personal Identity without Thought Experiments. (1988), p. 46, n. 28. Internet Archive.

This is Kathleen Wilkes, artfully highlighting the uncomfortable possibility conveniently left unmentioned in Star Trek. Her words are to our purpose too: if the transporter killed you, then you could discover this by trying it out, assuming there was such a thing as an afterlife. Of course, if there was no afterlife, then you’d learn nothing: you’d just lose consciousness and it’d be over. But the potential for falsification is clearly there since we cannot in general rule out an afterlife.

If falsification of teleportation is thus possible in principle, what of verification? What happens if the machine worked and really did “send” you to Mars? You’d press the button and find yourself waking up on Mars. Would this assure you in a parallel way that teleportation was real and that you really had been transported to Mars? Take Parfit’s account above:

Would this satisfy Parfit himself, if no one else, that the machine had worked? Would it constitute an empirical verification of teleportation?

As mentioned, the matter is not that simple, because of the following obvious snag. Even if the machine did work, and you did find yourself waking up on Mars, you’d be unable to tell (upon waking) whether you were the person who entered the machine, or whether that person died, and you were just a freshly-minted lookalike with false beliefs of having previously entered the machine. After all, anyone—real or copy—who emerged on Mars would “remember” having earlier entered the machine on Earth. So you’d be none the wiser as to whether you were “real” or “copy,” and thus none the wiser as to whether the machine had really worked.

For example, in Dan Dennett’s story, a woman on Mars with a broken spaceship uses a teleporter to get back to Earth. Upon reuniting with her daughter Sarah, it “hits her”:

So it seems that, if the machine worked, you could not discover this even by trying it out for yourself. This may be why the question is seldom discussed of whether teleportation is subject to empirical test. At least where verification of the phenomenon is concerned—and this is arguably the more important case—the answer may be thought to be obviously no.

This may be thought to settle the matter but, in fact, I will suggest now that the foregoing sceptical thoughts are somewhat confused and essentially incorrect. If the teleporter works, I believe that you can verify this by trying the machine out for yourself. Not always, as I will explain, but at least some of the time, when conditions are favourable in a certain way.

Menu

Can teleportation be verified empirically?

Can teleportation be verified empirically? What’s a logical paradox?

What’s a logical paradox? Achilles & the tortoise

Achilles & the tortoise The surprise exam

The surprise exam Newcomb’s problem

Newcomb’s problem Newcomb’s problem (sassy version)

Newcomb’s problem (sassy version) Seeing and being

Seeing and being Logic test!

Logic test! Philosophers say the strangest things

Philosophers say the strangest things Favourite puzzles

Favourite puzzles Books on consciousness

Books on consciousness Philosophy videos

Philosophy videos Phinteresting

Phinteresting Philosopher biographies

Philosopher biographies Philosopher birthdays

Philosopher birthdays Draft

Draftbarang 2009-2025  wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

April 2025

April 2025