Seeing and being

Preface

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain. But I have never liked this way of phrasing the problem because it strikes me that we have a poor grasp (to begin with) of the everyday phenomenon of seeing itself. —What is this thing we call seeing? So, in the essay, I explore instead the prior question of what we suppose the everyday phenomenon of seeing even to be—a question just as hard, but one which I find to be considerably more fruitful. And the only decent answer I can come up with suggests that a certain form of “neutral monism” may be the true relation between mind and body. Written in 2014.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

This is an essay on the “hard problem” of consciousness. If we focus on visual consciousness for simplicity, this is often said to be the problem of explaining how the everyday phenomenon we call seeing “arises” from the brain.

12. Seeing and being

The main lesson of the omnivisual being was that our need to distinguish seeing from being is closely entwined with our realization that we do not see everything.

That we do not see everything – that perception is partial – is therefore not an accident but something like an essential requirement for us to acquire the concepts of seeing and being at all. As we saw, a creature who saw everything would tend not to distinguish seeing from being in the same way that most of us tend not to distinguish a pain from its feeling.

This so far explains why we distinguish seeing from being but not what the distinction is. So what exactly is the distinction for someone who grasps that he does not see everything?

It seems to me that only one answer is possible here. Subject to one qualification, the concept of seeing is just the concept of partial being. I will explain the qualification below, but this points in the right direction quickly. It means that the relation between seeing and being is something like the relation between part and whole. This answer is liable to seem strange and unfamiliar, so let me spell it out slowly.

Let’s start with the fact that we always see the world from a certain perspective – that we only ever see a part of the world. The picture on the right, for example, captures that “bit” of the world seen by someone playing the black side of a game of chess.

This “bit” of the world is an example of what I mean by “partial being.” The term just refers to a spatio-temporal cross-section of physical reality, whose size and shape may vary from case to case. For simplicity, I will often speak of a spatial cross-section of reality, suppressing complications to do with time.

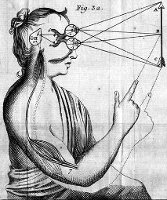

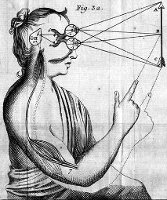

Where human vision is concerned, the relevant cross-section of physical reality will approximate the shape of an (infinite) cone, whose apex is located somewhere between the eyes, more or less.

Where human vision is concerned, the relevant cross-section of physical reality will approximate the shape of an (infinite) cone, whose apex is located somewhere between the eyes, more or less.

The nature of the cross-section will not actually matter much for now – it depends mainly on what sense-organ we are dealing with. Thus, an insect with compound eyes might encounter spherical cross-sections of reality, as would we if we considered the case of hearing, rather than seeing. But I will stick with human vision in what follows.

Terms like “cone” and “sphere” are also fairly rough. For example, we do not see everything within the cone of sight, even if we restrict ourselves to visibilia. Thus, we do not usually see the backs of objects within the cone, such as the back of the little boy in the picture above. Nor do we see the insides of most objects. Objects within the cone may also occlude one another, and so on. So the relevant cross-section for human vision is not quite a solid three-dimensional cone but only a restricted and odd-shaped portion thereof, involving various planar slices running along the length of the cone. I will say a little more about these cross-sections later, when it matters.

So much for the notion of partial being. Let me now explain the strange and unfamiliar thesis that the concept of seeing is just the concept of partial being – or that seeing is partial being, for short. The thesis is subject to one qualification, as mentioned, which I will introduce as well. It is best to approach the matter obliquely.

Consider first that, whenever you see, something happens which we might naively, but not altogether unnaturally, describe by saying that a partial world “comes into existence” for you. For example, the partial world captured in the photograph above is what “came into existence” for the chess player at the time in question.

This way of speaking is a little unusual or non-standard, but I think it is reasonably clear what it amounts to. Given the partiality of perception, there is a recognizable sense in which we “inhabit partial worlds” all the time, moving continuously and often seamlessly between them.

The point of introducing such funny or non-standard talk is to ask how it relates to our usual vocabulary of seeing and being. This question is not easy to answer but it is necessary to grapple with it.

We can start with the fact that such talk is non-standard. This is beyond doubt, since the chair in your room, for example, would not ordinarily be said to “come into existence” when you see it. We ordinarily accept rather that it already exists, so that what “comes into existence” when you see it – if we must speak in this way – is not the chair itself, but the seeing of the chair. This might be a suitable interpretation of what is really meant.

But – wait, no – this won’t do either because it runs into the diaphanousness of seeing. Thus, whatever this “seeing of the chair” is supposed to be that has allegedly “come into existence,” it appears to be undetectable or otherwise indiscernible. For, when you see the chair, nothing relevant seems to be “present” or to have “come into existence” except the chair itself – or a certain cross-section of it. No doubt, the seeing of the chair must somehow (also) enter the picture, but it is not easy to say how or where.

Well, now, perhaps the seeing of the chair is simply the “coming into existence” of the chair, rather than the entity that has “come into existence,” which we might as well just concede is the chair. But then we have just gone in a circle, since the concession takes us back to the original position – that what “comes into existence” is the chair – which we sensibly declined. Besides, the “coming into existence” of the chair presumably takes only a moment, but the seeing of the chair may clearly last for a while. During this while, the chair of course “remains in existence,” but then – as before – where is the seeing in all this, since all that remains is the chair?

(This line of thought is close to exasperating and some of our old difficulties are surfacing again, in particular that surrounding the diaphanousness of seeing.)

At this point, someone might complain that this funny person is simply using the word “exists” to mean “is seen.” When he says that the chair “comes into existence” when you look at it, all he means is that the chair comes to be seen. And when he says that the chair “remains in existence” for some while thereafter, all he means is that the chair continues to be seen. So it is indeed the chair that “comes into existence” and “remains in existence” on this way of speaking, but there is no longer any difficulty since the word “exist” is just being used in a funny way.

But I don’t think this will do either. Although this person talks in a strange way, it is a stretch to suppose that he has changed the meaning of the word “exist” so radically, or is otherwise using it in some idiosyncratic way. When he observes, for example, that we can recognize a sense in which the chair “comes into existence” when you see it, he is not likely to be trumpeting the tautology that the chair comes to be seen when you see it – what would be the point of this “observation”? So it doesn’t seem plausible that he is simply using “exists” to mean “is seen” – this is not a reasonable reading of his language. His language is strange, but not that strange.

Some philosophers have concluded from these and other more sophisticated considerations – which I won’t try to lay out here – that what “becomes present” or otherwise “comes into existence” when you see a chair is a facsimile or representation of the chair in your mind – a copy of the real thing – and that this is what the seeing of the chair really amounts to – the “coming into existence” of this facsimile in your mind. This is a version of the Galilean position mentioned previously, on which seeing consists of the occurrence of “colour sensations” or even a “colour movie” in your head. It continues to be unhelpful to us, however, for the same reason as before – it is no part of the layman’s way of thinking. To the layman, what “presents itself” to you when you see the chair is just the chair itself and not some facsimile or representation of the chair in either your mind or brain.

Some philosophers have concluded from these and other more sophisticated considerations – which I won’t try to lay out here – that what “becomes present” or otherwise “comes into existence” when you see a chair is a facsimile or representation of the chair in your mind – a copy of the real thing – and that this is what the seeing of the chair really amounts to – the “coming into existence” of this facsimile in your mind. This is a version of the Galilean position mentioned previously, on which seeing consists of the occurrence of “colour sensations” or even a “colour movie” in your head. It continues to be unhelpful to us, however, for the same reason as before – it is no part of the layman’s way of thinking. To the layman, what “presents itself” to you when you see the chair is just the chair itself and not some facsimile or representation of the chair in either your mind or brain.

Jerry Valberg, employing one of the sophisticated considerations alluded to above, has summarized what is essentially the same difficulty very simply as follows:

Let me now explain how I think this can be done. I will retain the notion of “coming into existence” – as used in the funny way above – since we want to see how it relates to our ordinary notions of seeing and being. To avoid confusion, however, I will speak instead of something “precipitating” whenever you see. For example – as before – whenever you see, something happens which we might naively describe by saying that a partial world “precipitates” for you.

This notion of a “precipitation” strikes me as being a relatively primitive one – the ur notion – out of which our ordinary notions of seeing and being are “cleaved.” I will explain the “cleaving” in a moment, but consider meanwhile that an omnivisual creature who fails to distinguish seeing from being can yet wield the ur notion in question. This creature would attach no sense to his seeing the world, or to the being of the world, but it can think – in a “neutral” way – of the world as having precipitated. This is the notion that remains if you “collapse” the notions of seeing and being, as it were. It is something of a Janus-faced notion because it contains the seeds of each of our ordinary notions of seeing and being.

Likewise, a boy who has yet to distinguish a pain from its feeling can nevertheless attend to the sudden and unwelcome “precipitation” when he stubs his toe and hobbles around in anguish. If he did make the distinction, he might be tempted to think of the precipitation as either the feeling of the pain or the being of the pain – vacillating in the same way we did above in considering whether it was the seeing or the being of the chair which precipitated when you looked at the chair. Indeed, feeling a pain seems to me completely parallel to seeing a chair, but I cannot really explore this parallel in this essay. But, here too, the precipitation is the neutral notion that one is left with if one “collapses” the feeling and the pain.

In these terms, the thesis I wish to defend may be stated more accurately as follows:

In terms of the original funny talk, what “comes into existence” when you see your chair is thus a certain cross-section of your chair, but also your seeing of the chair, these two things being one and the same. Strangely enough, then, your seeing of the chair is nothing more than the precipitated partial chair.

This so far just states the thesis – what motivates it may not be obvious. Its meaning may also be unclear because it is not natural for us to treat seeing as a thing, as in the slogan, “Seeing is precipitated partial being.” So let’s look past the slogan and elicit the thesis in a somewhat more natural way. We can do this by considering any old case of seeing and I’ll use a very simple one.

Imagine a creature looking at one side of a wall, trying to make sense of what is going on. Or think as before of its brain attempting its “best guess” as to what is transpiring.

Like Piaget’s child, the creature might first entertain some solipsistic hypothesis along the lines of, “This is all there is.” But, if it tries this, it won’t get very far, because it would then have to conclude that all that exists is one side of a wall, or something to this effect, which hypothesis we may assume makes no sense. —Reality might consist of a single wall, but not just one side of a wall.

So let’s suppose that the creature hypothesizes, more sensibly, that the side of the wall is just a part of what is “out there,” i.e., that there is more to “reality” than the current precipitation, e.g., a reverse side of the wall, at the very least.

In other words, the creature can begin to make sense of the precipitation in question by regarding it as an instance of partial being. At the same time, this “partial being” is none other than what the creature judges to be “seen.” So the creature grasps that it is confronted with a case of partial being, but also with a case of seeing. Given the diaphanousness of seeing, the conclusion now suggests itself – and I accordingly draw it – that to judge that something is seen is really nothing more than to judge that it is a case of partial being.

On this view, you don’t have to add anything to being to get a case of seeing, as a two-component model would tend to suggest. Quite the opposite – you get a case of seeing if you simply subtract from being in a suitable way. (See the cartoon.) I will explain the qualification ‘suitable’ later, since not any old subtraction will do, but this will not matter right now.

Put another way – and this is the clearest way of putting it – when you judge that you see something, you are essentially judging, “This is a cross-section of reality,” or, “This is just a part of reality,” or even simply, “There is more to reality than this.” Of course, that is not how you would normally express it. What you would normally say is just, “This is what I see.” On the proposed view, however, this is exactly the same judgement, only expressed in different words.

Note that the proposal goes beyond the mere partiality of perception. I am not just rehashing the observation that, whenever you see, you only see a part of reality. This is true, but I am also using this observation to advance an analysis of the concept of seeing. The analysis is that the concept of seeing something is just the concept that the something in question – i.e., whatever has precipitated – is an instance of partial being. This is the underlying meaning of the slogan that seeing is precipitated partial being.

Someone might object to the proposal on the grounds that it is one thing to judge that a certain demonstrable item is a part of reality and quite another to judge that it is seen. The creature, for example, might aver, “This thing that I see is just a part of reality,” employing both notions in an apparently reasonable way. On the proposed view, however, this assertion would contain a redundancy, since to say that the thing is seen is already to say that it is a part of reality. But the assertion does not strike one as redundant in that way. So something must be wrong with the view.

I am not moved by this objection, however, which, incidentally, bears traces of a two-component model of seeing. (One feels that one must add something to being to get seeing.) I am not moved because I have the partiality of perception on my side. Given the partiality of perception, it would be redundant to assert that whatever you see is only a part of reality. As we saw, barring certain exceptional cases – e.g., that of an omnivisual creature who has somehow been compelled to acquire the concepts of seeing and being – the thought that what one sees is just a part of reality will invariably be correct. So if the creature’s assertion does not seem redundant, one must not yet have grasped the fact of the partiality of perception.

The claim that seeing is (precipitated) partial being may also usefully be understood as the “converse” of the idealist thesis – something alluded to in the previous section. For an idealist like Berkeley, as mentioned, the physical world is just a bundle of sense experiences. I pointed out in the previous section that this is equivalent to claiming that a sense experience is just a slice of physical reality. And if we confine ourselves to visual experiences for simplicity, this is essentially the thesis that seeing is partial being.

The claim that seeing is (precipitated) partial being may also usefully be understood as the “converse” of the idealist thesis – something alluded to in the previous section. For an idealist like Berkeley, as mentioned, the physical world is just a bundle of sense experiences. I pointed out in the previous section that this is equivalent to claiming that a sense experience is just a slice of physical reality. And if we confine ourselves to visual experiences for simplicity, this is essentially the thesis that seeing is partial being.

As we saw, the idealist may decline the equivalence on the grounds that seeing is the ontologically prior notion, out of which being is “logically constructed.” My own view, as explained, is that seeing and being – more generally, mind and world – are ontological equals and that the claim that seeing is partial being is just as valid as the claim that being is a bundle of seeings. In fact, I think that these are “mutually supporting” claims, as I shall now explain.

The ontological parity is suggested by the way in which we arrived at the view. We saw that an omnivisual creature would lack both of the concepts of seeing and being, which suggests that a normally sighted creature would acquire them jointly, by “cleaving them apart,” as I put it earlier. We studied a number of such cleaving cases above – e.g., that of singing a song, or angle and side – so let’s pause to consider how seeing is cleaved apart from being, on the present view.

To a normally sighted creature, on the view being proposed, the notion of seeing is just the notion of (precipitated) partial being, and so the notion of seeing is clearly dependent upon that of being. But what, in turn, is the creature’s notion of being? Given that it possessed no such notion prior to acquiring the notion of seeing, but acquired it rather in the same breath, what does the notion amount to? It can’t just be the notion of a “precipitation” because an omnivisual being possesses that notion, but not that of being. Besides, that would not allow for the possibility of unseen being. Rather, continuing with our example above, it must have something to do with the creature’s judgement that there is “more to reality” than the side of the wall in question. What does “more to reality” here come down to?

Here, the sort of answer given by a classical phenomenalist like Mill is tailor-made for our purposes and I endorse it readily. To judge that there is “more to reality” than the current precipitation is just to judge that other precipitations are “counterfactually available” in some controllable or otherwise predictable way.

Here, the sort of answer given by a classical phenomenalist like Mill is tailor-made for our purposes and I endorse it readily. To judge that there is “more to reality” than the current precipitation is just to judge that other precipitations are “counterfactually available” in some controllable or otherwise predictable way.

This is comparable to playing a video game and forming a conception of the game world – e.g., a house with many rooms – by considering the changing images on the screen, which show different bits of the house each time. To the phenomenalist, the house is just the counterfactual availability of the screen images, assuming they “hang together” in some meaningful way. A realist, in contrast, would regard the house as an “intrinsic being” that transcends the images on the screen. For the realist, this transcendent being is what explains the counterfactual availability of the images, whereas the phenomenalist would tend to offer a different kind of “explanation.” (See below.) In the case of the video game, the screen images are no doubt explained by the underlying computer program, and so the realist may argue that the “house” is nothing more than that program. If so – and it is not clear that it is – then we should be realists about the world of a video game.

In the case of seeing, however, matters are even less clear. The realist would likewise claim that the physical world possesses an “intrinsic being” that transcends its evanescent precipitations. But it has always been unclear if we have any substantial conception of such “transcendent being” – i.e., beyond the minimal phenomenalist notion of counterfactual availablity. Even if this transcendent conception were available, we would still need to distinguish seeing from being in a way that was compatible with the diaphanousness of seeing, but I do not know of any way to do this – this is precisely the “insoluble” problem with which we began.

So I am willing to forego transcendent being in favour of counterfactual availability. I will say more about the realist notion below; for now, the phenomenalist notion is all we need. It seems to me entirely faithful to the way in which we learn about our world. For instance, we grasp the notion of things in space by noticing how everything “hangs together” as we move around. This involves counterfactual thinking of the sort, “If I do this, then that will come into view,” and so on, exactly as in a video game. In our terms, this refers to a “sufficiently predictable” or perhaps “sufficiently controllable” stream of precipitated partial being, i.e., a sufficiently controllable stream of seeing. Mill put it baldly by saying that matter is the permanent possibility of sensation. I will say instead that being is the permanent possibility of seeing – without implying thereby that seeing has the ontological priority. This is a version of the claim that being is a bundle of seeings, which was the idealist’s way of putting it.

And so the notion of being that we were trying to pin down is just the “permanent possibility of seeing,” which notion I believe may be attributed to the average layman. Such a notion must however draw upon a fairly sophisticated conceptual apparatus, as I mentioned above. Besides counterfactual notions, a grasp of time and agency would appear also to come into it. These are major metaphysical notions and I cannot here investigate what they amount to, let alone how they cohere with seeing and being. This is a large lacuna in the analysis, but one which I think is justifiable given our constraints. If we take these notions for granted, however, and avail ourselves of the “permanent possibility of seeing” – or potential seeing for short – then we have:

Seeing and being, on the other hand, turn out to be “mutually-dependent logical constructions” out of the notion of a precipitation. They are defined in terms of this notion in such a way that both must be grasped together, or not at all. (They feed off each other, as the two claims show.) This is the sense in which a precipitation is the root notion out of which seeing and being are cleaved, with the help of two other notions, “partiality” and “potentiality.” Someone who has cleaved seeing from being is just someone who has grasped the two claims above – if only to whatever inchoate extent that befits actual practice. An omnivisual being would never ordinarily entertain these claims because it would never ordinarily need to wield the notion of “partial being” or “potential seeing.”

We can return now to the man and the painting and answer the question that was asked previously.

We can return now to the man and the painting and answer the question that was asked previously.

In looking at the painting, why would this man need to entertain the seeing thought at all, “I see this painting before me?” Why – like Dretske’s dog – could he not simply manage with the being thought, “This painting is before me?”

The answer is that he cannot “make sense” of the painting and the wall on which it hangs – i.e., given the cross-sectional way in which he sees them – without regarding them as a part of a larger reality. But, once he has this thought, he automatically has the seeing thought, because that is essentially what the seeing thought amounts to, viz., “This is a part of a larger reality.”

Once we grasp this, we see that the same must be true of Dretske’s dog. Pace Dretske, dogs must have seeing thoughts as well, so long as we allow – as I think we must – that even dogs are familiar with the notion of “precipitated partial being.” For example, dogs, like many animals, know how to navigate complex spatial layouts and look around corners for interesting things that may be there, rather than where they presently are. This demonstrates a grasp of both precipitated partial being and potential seeing. So I should say that even dogs grasp the two claims above – however inchoately – and thus distinguish seeing from being. According to Dretske, a dog has the notion of being, but not that of seeing. On my view, this would be impossible as both notions feed off each other.

Our two claims were:

The main lesson of the omnivisual being was that our need to distinguish seeing from being is closely entwined with our realization that we do not see everything.

That we do not see everything – that perception is partial – is therefore not an accident but something like an essential requirement for us to acquire the concepts of seeing and being at all. As we saw, a creature who saw everything would tend not to distinguish seeing from being in the same way that most of us tend not to distinguish a pain from its feeling.

This so far explains why we distinguish seeing from being but not what the distinction is. So what exactly is the distinction for someone who grasps that he does not see everything?

It seems to me that only one answer is possible here. Subject to one qualification, the concept of seeing is just the concept of partial being. I will explain the qualification below, but this points in the right direction quickly. It means that the relation between seeing and being is something like the relation between part and whole. This answer is liable to seem strange and unfamiliar, so let me spell it out slowly.

Let’s start with the fact that we always see the world from a certain perspective – that we only ever see a part of the world. The picture on the right, for example, captures that “bit” of the world seen by someone playing the black side of a game of chess.

This “bit” of the world is an example of what I mean by “partial being.” The term just refers to a spatio-temporal cross-section of physical reality, whose size and shape may vary from case to case. For simplicity, I will often speak of a spatial cross-section of reality, suppressing complications to do with time.

The nature of the cross-section will not actually matter much for now – it depends mainly on what sense-organ we are dealing with. Thus, an insect with compound eyes might encounter spherical cross-sections of reality, as would we if we considered the case of hearing, rather than seeing. But I will stick with human vision in what follows.

Terms like “cone” and “sphere” are also fairly rough. For example, we do not see everything within the cone of sight, even if we restrict ourselves to visibilia. Thus, we do not usually see the backs of objects within the cone, such as the back of the little boy in the picture above. Nor do we see the insides of most objects. Objects within the cone may also occlude one another, and so on. So the relevant cross-section for human vision is not quite a solid three-dimensional cone but only a restricted and odd-shaped portion thereof, involving various planar slices running along the length of the cone. I will say a little more about these cross-sections later, when it matters.

So much for the notion of partial being. Let me now explain the strange and unfamiliar thesis that the concept of seeing is just the concept of partial being – or that seeing is partial being, for short. The thesis is subject to one qualification, as mentioned, which I will introduce as well. It is best to approach the matter obliquely.

Consider first that, whenever you see, something happens which we might naively, but not altogether unnaturally, describe by saying that a partial world “comes into existence” for you. For example, the partial world captured in the photograph above is what “came into existence” for the chess player at the time in question.

This way of speaking is a little unusual or non-standard, but I think it is reasonably clear what it amounts to. Given the partiality of perception, there is a recognizable sense in which we “inhabit partial worlds” all the time, moving continuously and often seamlessly between them.

The point of introducing such funny or non-standard talk is to ask how it relates to our usual vocabulary of seeing and being. This question is not easy to answer but it is necessary to grapple with it.

We can start with the fact that such talk is non-standard. This is beyond doubt, since the chair in your room, for example, would not ordinarily be said to “come into existence” when you see it. We ordinarily accept rather that it already exists, so that what “comes into existence” when you see it – if we must speak in this way – is not the chair itself, but the seeing of the chair. This might be a suitable interpretation of what is really meant.

But – wait, no – this won’t do either because it runs into the diaphanousness of seeing. Thus, whatever this “seeing of the chair” is supposed to be that has allegedly “come into existence,” it appears to be undetectable or otherwise indiscernible. For, when you see the chair, nothing relevant seems to be “present” or to have “come into existence” except the chair itself – or a certain cross-section of it. No doubt, the seeing of the chair must somehow (also) enter the picture, but it is not easy to say how or where.

Well, now, perhaps the seeing of the chair is simply the “coming into existence” of the chair, rather than the entity that has “come into existence,” which we might as well just concede is the chair. But then we have just gone in a circle, since the concession takes us back to the original position – that what “comes into existence” is the chair – which we sensibly declined. Besides, the “coming into existence” of the chair presumably takes only a moment, but the seeing of the chair may clearly last for a while. During this while, the chair of course “remains in existence,” but then – as before – where is the seeing in all this, since all that remains is the chair?

(This line of thought is close to exasperating and some of our old difficulties are surfacing again, in particular that surrounding the diaphanousness of seeing.)

At this point, someone might complain that this funny person is simply using the word “exists” to mean “is seen.” When he says that the chair “comes into existence” when you look at it, all he means is that the chair comes to be seen. And when he says that the chair “remains in existence” for some while thereafter, all he means is that the chair continues to be seen. So it is indeed the chair that “comes into existence” and “remains in existence” on this way of speaking, but there is no longer any difficulty since the word “exist” is just being used in a funny way.

But I don’t think this will do either. Although this person talks in a strange way, it is a stretch to suppose that he has changed the meaning of the word “exist” so radically, or is otherwise using it in some idiosyncratic way. When he observes, for example, that we can recognize a sense in which the chair “comes into existence” when you see it, he is not likely to be trumpeting the tautology that the chair comes to be seen when you see it – what would be the point of this “observation”? So it doesn’t seem plausible that he is simply using “exists” to mean “is seen” – this is not a reasonable reading of his language. His language is strange, but not that strange.

Jerry Valberg, employing one of the sophisticated considerations alluded to above, has summarized what is essentially the same difficulty very simply as follows:

As before, the difficulty is that of coming to terms with this not altogether unnatural talk of something “coming into existence” – Valberg speaks of its “presence” – whenever you see. If we can reconcile this way of talking with our ordinary talk of “seeing” and “being,” we will improve our understanding of these notions.This object, the object present to me when I look at the book, cannot be the book. It cannot be the book because [given that visual experience is a causal product of brain activity] it could survive the elimination of the book. So it, this object, is an internal object, something which exists only in so far as it is present in my experience. But wait, this object is a book. The object present to me when I look at the book on the table is the book on the table. There is nothing else there. Now I realize that, as a contribution to philosophy, thoughts of this sort may appear a trifle quick and simple-minded; yet it is precisely such thoughts that come over me. (The Puzzle of Experience, p. 21.)

Let me now explain how I think this can be done. I will retain the notion of “coming into existence” – as used in the funny way above – since we want to see how it relates to our ordinary notions of seeing and being. To avoid confusion, however, I will speak instead of something “precipitating” whenever you see. For example – as before – whenever you see, something happens which we might naively describe by saying that a partial world “precipitates” for you.

This notion of a “precipitation” strikes me as being a relatively primitive one – the ur notion – out of which our ordinary notions of seeing and being are “cleaved.” I will explain the “cleaving” in a moment, but consider meanwhile that an omnivisual creature who fails to distinguish seeing from being can yet wield the ur notion in question. This creature would attach no sense to his seeing the world, or to the being of the world, but it can think – in a “neutral” way – of the world as having precipitated. This is the notion that remains if you “collapse” the notions of seeing and being, as it were. It is something of a Janus-faced notion because it contains the seeds of each of our ordinary notions of seeing and being.

Likewise, a boy who has yet to distinguish a pain from its feeling can nevertheless attend to the sudden and unwelcome “precipitation” when he stubs his toe and hobbles around in anguish. If he did make the distinction, he might be tempted to think of the precipitation as either the feeling of the pain or the being of the pain – vacillating in the same way we did above in considering whether it was the seeing or the being of the chair which precipitated when you looked at the chair. Indeed, feeling a pain seems to me completely parallel to seeing a chair, but I cannot really explore this parallel in this essay. But, here too, the precipitation is the neutral notion that one is left with if one “collapses” the feeling and the pain.

In these terms, the thesis I wish to defend may be stated more accurately as follows:

Seeing is precipitated partial being.

This means that, in seeing your chair, what precipitates for you may be regarded as either of the following because they are exactly the same thing:A certain cross-section of the chair – i.e., a certain partial being;

Your seeing of the chair.

In other words, so long as we remain within the realm of a precipitation, seeing is identical to partial being.Note. ‘Within the realm of a precipitation’ is the qualification alluded to earlier. Outside the realm of a precipitation, there is no such thing as seeing. (I hope this is obvious.) Accordingly, outside this realm, no cases of partial being – of which there presumably are plenty – should count as cases of seeing. So my initial bald statement that seeing is partial being was just rough, to point ahead quickly.

In terms of the original funny talk, what “comes into existence” when you see your chair is thus a certain cross-section of your chair, but also your seeing of the chair, these two things being one and the same. Strangely enough, then, your seeing of the chair is nothing more than the precipitated partial chair.

This so far just states the thesis – what motivates it may not be obvious. Its meaning may also be unclear because it is not natural for us to treat seeing as a thing, as in the slogan, “Seeing is precipitated partial being.” So let’s look past the slogan and elicit the thesis in a somewhat more natural way. We can do this by considering any old case of seeing and I’ll use a very simple one.

Imagine a creature looking at one side of a wall, trying to make sense of what is going on. Or think as before of its brain attempting its “best guess” as to what is transpiring.

Like Piaget’s child, the creature might first entertain some solipsistic hypothesis along the lines of, “This is all there is.” But, if it tries this, it won’t get very far, because it would then have to conclude that all that exists is one side of a wall, or something to this effect, which hypothesis we may assume makes no sense. —Reality might consist of a single wall, but not just one side of a wall.

So let’s suppose that the creature hypothesizes, more sensibly, that the side of the wall is just a part of what is “out there,” i.e., that there is more to “reality” than the current precipitation, e.g., a reverse side of the wall, at the very least.

Note. Arriving at this hypothesis would be a fairly sophisticated achievement, as we know from the cognitive development of infants. Counterfactual considerations, among other things, must surely come into it. (I will say more on this below.)

In other words, the creature can begin to make sense of the precipitation in question by regarding it as an instance of partial being. At the same time, this “partial being” is none other than what the creature judges to be “seen.” So the creature grasps that it is confronted with a case of partial being, but also with a case of seeing. Given the diaphanousness of seeing, the conclusion now suggests itself – and I accordingly draw it – that to judge that something is seen is really nothing more than to judge that it is a case of partial being.

On this view, you don’t have to add anything to being to get a case of seeing, as a two-component model would tend to suggest. Quite the opposite – you get a case of seeing if you simply subtract from being in a suitable way. (See the cartoon.) I will explain the qualification ‘suitable’ later, since not any old subtraction will do, but this will not matter right now.

Put another way – and this is the clearest way of putting it – when you judge that you see something, you are essentially judging, “This is a cross-section of reality,” or, “This is just a part of reality,” or even simply, “There is more to reality than this.” Of course, that is not how you would normally express it. What you would normally say is just, “This is what I see.” On the proposed view, however, this is exactly the same judgement, only expressed in different words.

Note that the proposal goes beyond the mere partiality of perception. I am not just rehashing the observation that, whenever you see, you only see a part of reality. This is true, but I am also using this observation to advance an analysis of the concept of seeing. The analysis is that the concept of seeing something is just the concept that the something in question – i.e., whatever has precipitated – is an instance of partial being. This is the underlying meaning of the slogan that seeing is precipitated partial being.

Someone might object to the proposal on the grounds that it is one thing to judge that a certain demonstrable item is a part of reality and quite another to judge that it is seen. The creature, for example, might aver, “This thing that I see is just a part of reality,” employing both notions in an apparently reasonable way. On the proposed view, however, this assertion would contain a redundancy, since to say that the thing is seen is already to say that it is a part of reality. But the assertion does not strike one as redundant in that way. So something must be wrong with the view.

I am not moved by this objection, however, which, incidentally, bears traces of a two-component model of seeing. (One feels that one must add something to being to get seeing.) I am not moved because I have the partiality of perception on my side. Given the partiality of perception, it would be redundant to assert that whatever you see is only a part of reality. As we saw, barring certain exceptional cases – e.g., that of an omnivisual creature who has somehow been compelled to acquire the concepts of seeing and being – the thought that what one sees is just a part of reality will invariably be correct. So if the creature’s assertion does not seem redundant, one must not yet have grasped the fact of the partiality of perception.

As we saw, the idealist may decline the equivalence on the grounds that seeing is the ontologically prior notion, out of which being is “logically constructed.” My own view, as explained, is that seeing and being – more generally, mind and world – are ontological equals and that the claim that seeing is partial being is just as valid as the claim that being is a bundle of seeings. In fact, I think that these are “mutually supporting” claims, as I shall now explain.

The ontological parity is suggested by the way in which we arrived at the view. We saw that an omnivisual creature would lack both of the concepts of seeing and being, which suggests that a normally sighted creature would acquire them jointly, by “cleaving them apart,” as I put it earlier. We studied a number of such cleaving cases above – e.g., that of singing a song, or angle and side – so let’s pause to consider how seeing is cleaved apart from being, on the present view.

To a normally sighted creature, on the view being proposed, the notion of seeing is just the notion of (precipitated) partial being, and so the notion of seeing is clearly dependent upon that of being. But what, in turn, is the creature’s notion of being? Given that it possessed no such notion prior to acquiring the notion of seeing, but acquired it rather in the same breath, what does the notion amount to? It can’t just be the notion of a “precipitation” because an omnivisual being possesses that notion, but not that of being. Besides, that would not allow for the possibility of unseen being. Rather, continuing with our example above, it must have something to do with the creature’s judgement that there is “more to reality” than the side of the wall in question. What does “more to reality” here come down to?

This is comparable to playing a video game and forming a conception of the game world – e.g., a house with many rooms – by considering the changing images on the screen, which show different bits of the house each time. To the phenomenalist, the house is just the counterfactual availability of the screen images, assuming they “hang together” in some meaningful way. A realist, in contrast, would regard the house as an “intrinsic being” that transcends the images on the screen. For the realist, this transcendent being is what explains the counterfactual availability of the images, whereas the phenomenalist would tend to offer a different kind of “explanation.” (See below.) In the case of the video game, the screen images are no doubt explained by the underlying computer program, and so the realist may argue that the “house” is nothing more than that program. If so – and it is not clear that it is – then we should be realists about the world of a video game.

In the case of seeing, however, matters are even less clear. The realist would likewise claim that the physical world possesses an “intrinsic being” that transcends its evanescent precipitations. But it has always been unclear if we have any substantial conception of such “transcendent being” – i.e., beyond the minimal phenomenalist notion of counterfactual availablity. Even if this transcendent conception were available, we would still need to distinguish seeing from being in a way that was compatible with the diaphanousness of seeing, but I do not know of any way to do this – this is precisely the “insoluble” problem with which we began.

So I am willing to forego transcendent being in favour of counterfactual availability. I will say more about the realist notion below; for now, the phenomenalist notion is all we need. It seems to me entirely faithful to the way in which we learn about our world. For instance, we grasp the notion of things in space by noticing how everything “hangs together” as we move around. This involves counterfactual thinking of the sort, “If I do this, then that will come into view,” and so on, exactly as in a video game. In our terms, this refers to a “sufficiently predictable” or perhaps “sufficiently controllable” stream of precipitated partial being, i.e., a sufficiently controllable stream of seeing. Mill put it baldly by saying that matter is the permanent possibility of sensation. I will say instead that being is the permanent possibility of seeing – without implying thereby that seeing has the ontological priority. This is a version of the claim that being is a bundle of seeings, which was the idealist’s way of putting it.

And so the notion of being that we were trying to pin down is just the “permanent possibility of seeing,” which notion I believe may be attributed to the average layman. Such a notion must however draw upon a fairly sophisticated conceptual apparatus, as I mentioned above. Besides counterfactual notions, a grasp of time and agency would appear also to come into it. These are major metaphysical notions and I cannot here investigate what they amount to, let alone how they cohere with seeing and being. This is a large lacuna in the analysis, but one which I think is justifiable given our constraints. If we take these notions for granted, however, and avail ourselves of the “permanent possibility of seeing” – or potential seeing for short – then we have:

Seeing is (precipitated) partial being;

Being is potential seeing.

This pair of claims constitutes the overall position of this essay. The notion of a precipitation may be regarded as primitive – or perhaps relatively primitive, since I believe it can ultimately be elucidated. This is not the best time to try this though. (I will suggest something in the final section.)Being is potential seeing.

Seeing and being, on the other hand, turn out to be “mutually-dependent logical constructions” out of the notion of a precipitation. They are defined in terms of this notion in such a way that both must be grasped together, or not at all. (They feed off each other, as the two claims show.) This is the sense in which a precipitation is the root notion out of which seeing and being are cleaved, with the help of two other notions, “partiality” and “potentiality.” Someone who has cleaved seeing from being is just someone who has grasped the two claims above – if only to whatever inchoate extent that befits actual practice. An omnivisual being would never ordinarily entertain these claims because it would never ordinarily need to wield the notion of “partial being” or “potential seeing.”

In looking at the painting, why would this man need to entertain the seeing thought at all, “I see this painting before me?” Why – like Dretske’s dog – could he not simply manage with the being thought, “This painting is before me?”

The answer is that he cannot “make sense” of the painting and the wall on which it hangs – i.e., given the cross-sectional way in which he sees them – without regarding them as a part of a larger reality. But, once he has this thought, he automatically has the seeing thought, because that is essentially what the seeing thought amounts to, viz., “This is a part of a larger reality.”

Once we grasp this, we see that the same must be true of Dretske’s dog. Pace Dretske, dogs must have seeing thoughts as well, so long as we allow – as I think we must – that even dogs are familiar with the notion of “precipitated partial being.” For example, dogs, like many animals, know how to navigate complex spatial layouts and look around corners for interesting things that may be there, rather than where they presently are. This demonstrates a grasp of both precipitated partial being and potential seeing. So I should say that even dogs grasp the two claims above – however inchoately – and thus distinguish seeing from being. According to Dretske, a dog has the notion of being, but not that of seeing. On my view, this would be impossible as both notions feed off each other.

Our two claims were:

Seeing is (precipitated) partial being;

Being is potential seeing.

The first claim deserves further elaboration, but let me first say something about the second claim that is the broad phenomenalist dictum.

Being is potential seeing.

Menu

What’s a logical paradox?

What’s a logical paradox? Achilles & the tortoise

Achilles & the tortoise The surprise exam

The surprise exam Newcomb’s problem

Newcomb’s problem Newcomb’s problem (sassy version)

Newcomb’s problem (sassy version) Seeing and being

Seeing and being Logic test!

Logic test! Philosophers say the strangest things

Philosophers say the strangest things Favourite puzzles

Favourite puzzles Books on consciousness

Books on consciousness Philosophy videos

Philosophy videos Phinteresting

Phinteresting Philosopher biographies

Philosopher biographies Philosopher birthdays

Philosopher birthdays Draft

Draftbarang 2009-2025  wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine

wayback machine